The following excerpt appears in sections of CrossFit Games champion Mat Fraser’s new book, HWPO: Hard Work Pays Off: Transform Your Body and Your Mind with CrossFit’s Five-Time Fittest Man on Earth, co-written with Spenser Mestel. The book combines aspects of a memoir and a training manual to help you learn from the five-time World’s Fittest Man.

THE DECISION TO KEEP competing after the 2015 season seems so obvious now, but that’s not how I felt at the end of that year’s CrossFit Games.

After the last event, while I was still gasping for air, I lay down on a supply cart in the athlete tunnel and replayed in my head all the mistakes I’d made. A few had been purely physical. I couldn’t sprint. I could barely swim. Of all the guys on the field, I had one of the weakest deadlifts.

But the worst ones had been mental. When we had to flip the 560-pound “Pig” down the soccer field for the eighth event, I couldn’t figure out the right technique, so I panicked. I did most of the work with my biceps, gassed myself out, and gave up a huge part of my lead. Then I got rattled again on the last event. After I failed one handstand push-up after another, I never thought to take a break, recover, and readjust the parallettes. So I kept failing, and even going full dummy on the Assault Bike and rower wasn’t enough. For the second year in a row, I came in second.

I was disappointed, humiliated, and ready to quit. I knew that I’d lost—or maybe it’s more accurate to say that I’d choked— because I’d cut corners, and if I wanted to make another run at the Games, I’d have to be all in. Obviously, that meant more training in my tiny home gym, by myself, with no one around to slap me on the ass and tell me “good job.” I’d also have to stop thinking I was the expert and seek out new coaches to help me attack my weaknesses, which was why the first step to a comeback would be so brutal. I’d have to do what I did after every competition: watch the footage and create a list of everything that I’d done wrong. Did I really want to become a champion that badly?

I mean, this wasn’t the first dream that hadn’t panned out for me. After a decade of weightlifting and years at the Olympic Training Center, I didn’t make the Olympic team, and that didn’t kill me, right? Plus, I had two university degrees, and even though I’d hated my summer internship at an aerospace company, I was sure I could find an engineering job I liked. Or I could even go back to working in the oil fields in Alberta.

I didn’t have to kill myself in the gym every day. I didn’t have to keep doing rowing intervals that were so intense I left literal puddles of sweat on the floor. I didn’t have to restructure my life around one singular goal: to win the CrossFit Games.

I wanted a normal life. I wanted to go to my friend’s bachelor party without worrying about missing training, drive to Rhode Island to see my girlfriend whenever I felt like it, and spend my rest days waterskiing, not on top of a lacrosse ball for twelve hours rolling out the tension in my muscles.

I’m sure these excuses sound familiar. They’re what you tell yourself when you’re too tired to make the 7 a.m. class or too hungover to even consider a Sunday-morning lifting session. They’re the excuses everyone makes, and I made them all throughout the 2015 season.

But then I changed. Lying on that supply cart after the last event, choking back tears as the other competitors streamed past, I knew I never again wanted to feel as low as I did in that moment. To avoid that possibility completely, I had two options: I could quit CrossFit altogether and start looking for a desk job.

Or I could radically transform my mindset. Every choice I was faced with, I would ask myself whether it would help me win the CrossFit Games. No? Then I wouldn’t do it.

And now, after eight years in the sport, I’m the most successful competitive CrossFit athlete in history. I’ve won more events (29), more titles (5 in a row), and by the largest margins of anyone in the sport.

While there are some guys who might beat me in a single workout, no one can say they’re a better all-around athlete. Weightlifting, gymnastics, kettlebells, running, swimming, rowing, strongman: I’ve relentlessly trained them all, so now you don’t have to guess how to.

While competing, I would never have offered this information and risked giving the other athletes an edge. But now that I’ve decided to retire from professional CrossFit, I can finally share with you how I prepared my body and trained my mind.

Needless to say, it won’t be easy. After the 2015 Games, I bought my own Pig and flipped it every night after everyone had gone home. The impact from catching the 560-pound mat was so intense on my hands that I went to the doctor and got X-rays. He thought I’d punched a wall with both fists.

Except for a few weeks I’d take off in August, every day for the past five years was roughly the same: wake up earlier than I’d like, sell my soul to the Assault Bike and the swimming intervals and the 40-minute AMRAPs, eat, sleep, repeat.

But it absolutely was worth it. CrossFit is how I met my best friends, business partners, and even my wife. CrossFit is how I found the artist who tattooed my chest, how I was able to travel across the world, and how I bought our home. CrossFit is also one of the most supportive communities I’ve ever been a part of.

During the Games, when I was on the competition floor trying to hold on to the barbell for the last few reps of the workout and so overheated that my head felt like it was being crushed in a vise, it was the fans who helped me get across the finish line.

So what I’m telling you is something you’ve already heard but may not fully understand: Hard work pays off.

STRENGTH

For my first five years of weightlifting, every part of my training was focused on technique. My starting position, my pull from the ground, my bar path as it traveled up—everything had to be perfect, and I hated it. I started weightlifting because I wanted to get jacked, not to have the best form. But now, almost a decade after I quit that sport, I see how much that foundation paid off.

Just by looking at a workout, I know exactly how to adjust my technique. If the weight is light and the reps are high, I can shorten my movement and cycle the bar as quickly as possible. If the weight is heavy or I need to recover, I can switch to slow, efficient single reps. And whether I’m fresh or at the end of a workout, I never need to worry about not meeting the movement standards—the infamous “no rep.”

However, technique alone wasn’t enough to make me great. When I went to the Olympic Training Camp, I was the weakest guy by far, which is how I ended up breaking my back in two places. From then all the way through my CrossFit career, I’ve had to dedicate myself to strength—sometimes to the exclusion of all else. It’s a long, repetitive process, but to be your best self, you need both strength and technique.

I’m here to teach you both.

My weightlifting career began by accident. In middle school, my best friend and I were on the football team, and for a few days each week, we’d get to lift with the high school guys. There was no training program to follow, so each session we’d max out our bench press and do bicep curls until we failed. At that age, your body’s growing so quickly that you don’t need good form to get stronger. Almost every time I lifted, I’d hit a new personal record.

During one of these sessions, a football coach saw my passion and suggested to my dad, who along with my mom was a former Olympic athlete, that I train at an actual weightlifting club. At the time, I had no clue how any of the movements were supposed to look, and I didn’t even know I was already doing a “clean and jerk.” I just thought it was cool to get the barbell from the ground over my head.

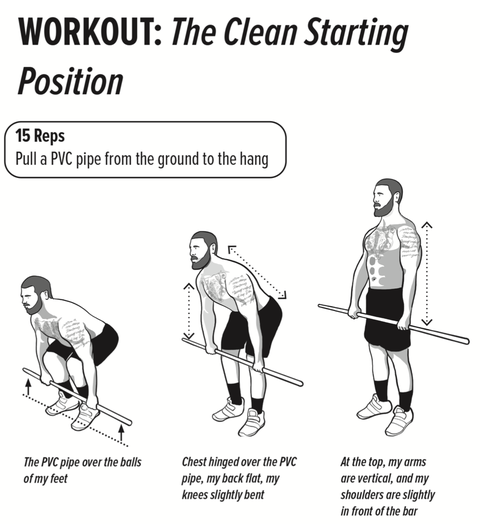

When my dad and I walked into that weightlifting club in Essex, Vermont, it was nothing like what I’d expected. For starters, no one looked like the guys I had seen getting pumped at Muscle Beach. They weren’t absolutely shredded, and a lot of them weren’t even lifting weights. Instead, they had a PVC pipe in their hands and would do nothing more than bend forward at the waist and stand. Bend at the waist and stand. I didn’t even see a rack of dumbbells, just a narrow room with white walls, drop ceilings, and twelve platforms made of unfinished plywood.

I expected I’d train like we did at football practice—no supervision, no form, just lifting as much as I could and dropping the bar when it was too much. Instead, Coach Polakowski told me to grab a broomstick.

For the next few weeks, all I worked on was the starting positions, which differ slightly depending on which of the two Olympic lifts you’re doing: the snatch, where you get the barbell from the ground over your head in one motion, or the clean and jerk, where the bar goes first from the ground to your shoulders and then overhead.

ENDURANCE

Before Regionals in 2013, I’d started lifting at Champlain Valley but refused to try a “real” CrossFit workout. I’d mess around with the weightlifting workouts, like Heavy Grace, but never anything with even a hint of cardio. I’d done a sport where you rest for minutes in between sets, so why would I want to run or row or get on a bike at all, let alone between the other movements?

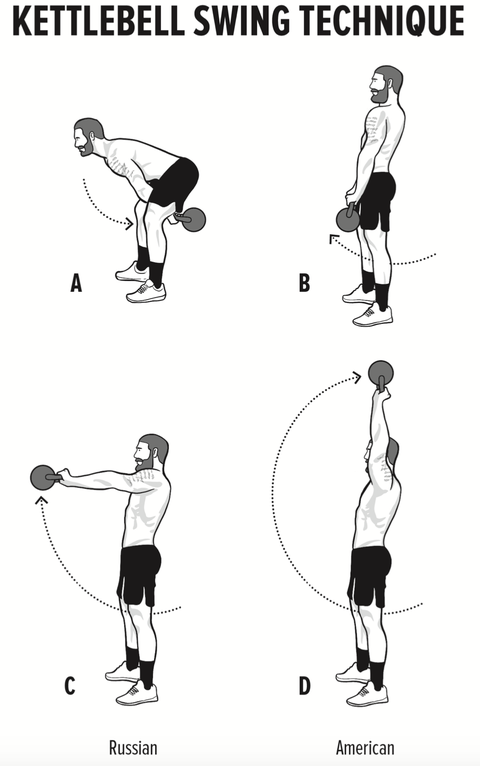

It sounded miserable, and when I finally got talked into doing a METCON (metabolic conditioning) of kettlebell swings and running, it was just as bad as I’d expected.

I could do the swings as quickly as humanly possible. I knew from Olympic lifting how to hinge forward and hike the bell behind me, then how to stand up and thrust my hips forward to get it above my head. I finished those sets well before everyone else—but they all caught me on the run. In fact, it looked like some of them even recovered a bit as they jogged past me. How was that possible?

It was hard to understand at first. Time had just never been crucial to my success before. Yeah, you had to finish your Olympic lift within the 60 seconds, but I could pump my hips 20 times and still make that cutoff. So having to complete a workout as quickly as possible was similar to adding an entirely new field to the scorecard, like a dance contest after the snatch and clean and jerk at an Olympic weightlifting meet. I could learn to do it eventually, but it would take a long time.

SPEED

After the heartbreak of narrowly losing the 2015 Games, I took stock of my physical weaknesses: My deadlift was barely competitive. I couldn’t swim in open water. I was afraid of long sets of toes-to-bar. But there was one movement that I knew needed more work than all the others combined: my sprinting.

I took 37th out of 39 in the sprint event, and my running technique was so bad that Coach Polakowski reached out to me afterward. We’d always worked together on weightlifting, but he considered himself a track coach who used lifting as a tool and offered to let me join his track team. I was grateful for the help and agreed, not exactly realizing that I’d be running with my town’s middle and high school kids.

It was before the spring season, when the Vermont winter was still too crushing to train outside, so all of us—the dozens of kids from the middle and high school—were crammed into the indoor gym. I could tell that everyone was staring at me, probably assuming that I was a new assistant coach, but when Coach Pol blew his whistle, I lined up with everyone else and did the butt kickers, high knees, and heel walks.

Over the next few months, my sprinting got better, but those improvements also made me realize that speed is about much more than stepping up and driving down. I started to look for hacks everywhere else, from how I loaded the strongman yoke to whether I did a burpee and touched the rings with the front of my hands or the back.

In that way, speed isn’t just how fast you can run 100 meters or do butterfly pullups. It’s a mindset that you have to apply to everything.

I trained with the Essex high school team two to three times a week for about four months, and it turns out that sprinting is like Olympic weightlifting in three important ways.

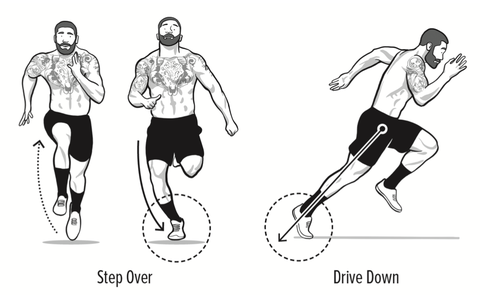

For one, technique is everything, and what I was doing during the suicide sprints in 2015 was totally backward. I figured that you’d want to reach your front foot out as far as possible to cover a lot of ground, right? Wrong. I also thought that you should land with your toe first so you had plenty of cushion to rebound off. Wrong again. And finally, it seemed obvious that you’d need to keep tension throughout your torso and diaphragm to give you more power. Most wrong of all. In terms of your stride, the goal is to punch the ground and generate as much force as possible. To do that, when you bring your tail leg up, you want to step over the opposite knee and then drive that foot down into the ground so it lands directly under- neath you with your toe pulled up toward the sky. Step over, drive down. Step over, drive down. Your stride will be shorter, but the net effect is a faster sprint. And once you’ve mastered the lower- body technique, you can focus on the upper body.

Just like with Olympic lifting, it’s best to relax under tension. Imagine trying to snatch with your triceps flexed the entire time. It’d be impossible, and the same thing is true for sprinting. The more you tense your arms and scrunch your face and try to go faster, the slower you’ll end up. To make sure you aren’t running with your elbows out wide or your shoulders hunched into your ears, set up a camera and film yourself.

COORDINATION

My parents were surprised when I stood up at six months old! At that age, babies are working on the stability to just sit on their own in a tripod position, but there I was, crawling and getting to my feet.

Three months later, I started walking, but I didn’t have the coordination or strength to lower myself to the ground. Instead, I would timber straight back, whack my head on the carpet, then do it all over again. Eventually, my parents took a roll of foam and wrapped it around my head like a foam helmet. It was held together with a long sticker from my dad’s real estate business so it looked like I had a name on my head. They would put this on my head when I got up each day and off I’d go.

As basic as it seems, being able to get off the ground and stand up is a great way to start improving your coordination, and the Turkish get-up will teach you two core principles. The first is how you can use tension to stabilize your body. That same technique is also how you’ll eventually learn how to cycle your pull-ups in one fluid “butterfly” motion.

The second principle is how to keep your body aligned. Especially as you go up in weight with the Turkish get-up, you have to make sure the kettlebell in your hand is stacked on top of your shoulder, which is a position that will keep your joints safe in other movements, like handstand push-ups. So be diligent with your get-ups (foam helmet not necessary).

As I got older, I learned a lot of sports quickly. I swam across our 36-foot outdoor pool in one breath when I was four. I could walk for a dozen steps on my hands when I was seven. I was playing soccer, wrestling, Rollerblading, ice skating, and skiing double black diamonds by the time I was nine. CrossFit hadn’t been invented yet, but even if it had, I’m not sure I would have benefited from starting that young.

With gyms offering classes especially for kids, and a teen division at the Games for athletes as young as fifteen, you’re able to train CrossFit earlier and earlier. I think that’s great, but it’s also important to figure out what you like and what you don’t. Both my parents were Olympic figure skaters for Canada. Naturally, I tried skating as a kid (I actually performed in my first ice show with them when I was four), but it wasn’t for me, and my parents didn’t push it.

When it came to quitting or changing sports, my parents only had one rule: Once we’d committed to something, we’d finish out that season. So I tried pretty much everything I could. What stuck was Olympic lifting (obviously), but I also played football, and I regret taking my junior year off from football so that I could train more weightlifting. Even if I wasn’t destined for the NFL, I still loved playing, and it probably would’ve helped me at the Games. In fact, one of the main tenets of CrossFit is that you “regularly learn and play new sports,” so try something new. Pick up surfing or golf or anything else that challenges you to move in unfamiliar ways and helps you avoid plateauing.

MENTALITY

I love to train scared, so I was really in my element in the lead-up to the 2016 Regionals.

Unlike at the Games, the events for Regionals are announced a few weeks ahead of time, so obviously you practice them beforehand. And I don’t mean you do them half-assed at the end of the day. I’d approach them as seriously as if they were the final event at the Games and bury myself trying to get the best score.

Of the seven Regionals workouts in 2016, I was pretty satisfied with six, but there was one I couldn’t finish: Strict Nate—10 rounds of 4 strict muscle-ups, 7 strict handstand pushups, and 12 kettlebell snatches. I did it a few times, and the best I ever got was seven rounds and change. That didn’t feel great at first but wasn’t a disaster because some workouts are specifically designed to be unbeatable. Then I realized that this wasn’t one of them.

Usually, I’d never share any information about my training—you’ve always got to maintain that edge—but that year I was swapping scores with Alex Anderson, who was competing in a different region. During practice, his Strict Nate score was better than mine, and I watched as other guys posted videos of their attempts on Instagram. It seemed like everyone was finishing but me.

Okay, I tried to reassure myself. You can upload whatever you want to social media, but all that matters is what happens on the floor. And, because I was in the third and final region to compete that year, I’d have the advantage of seeing them all attempt Strict Nate before I did.

Six guys finished it in the first week, and seven more the week after. Yikes, I told myself. This is the year you don’t qualify. This is the year you don’t have what it takes. I could already hear people talking about why I’d fallen off and how I just didn’t have what it took to stand on top of the podium.

So when I finally got to Regionals, it didn’t matter that I won the first event. As the countdown started for Nasty Nate, I knew I was about to be embarrassed, so I refused to relent for even a second. No extra-long chalk breaks. No dropping into a squat and catching my breath. If I wanted a shot at the Games that year, I had to drive full speed into the pain cave.

At the same time, I couldn’t watch what the other competitors were doing and change my pace to race them. I had to “stay in my lane” and get the best score for me.

I ended up finishing the workout in 18:30—almost 50 percent faster than in practice. It was such an unbelievable improvement that Alex was convinced I’d lied to him. I hadn’t. I just tend to do my best when I feel like my back is against the wall.

Well, kind of.

I wish I could say that my mental prep is as straightforward as training scared, but it’s more complicated than that. For me to be the best version of myself, I have to simultaneously believe that I’m overrated and invincible, that I’m an impostor on the verge of being humiliated on the competition floor, and that I’m an untouchable Lamborghini in a sea of broken-down hoopties.