Too many people struggling with serious mental illness and addiction continue to bike through overcrowded San Francisco emergency rooms, unable to get long-term help, according to city officials.

Frustrated city health workers and public hospital leaders shed light on the crisis, which comes despite a slew of new programs and massive behavioral health funding, during a public hearing Thursday.

In one example, just five people in the past five years had at least 1,781 ambulance transports costing more than $4 million, said April Sloan, who oversees fire department paramedic teams that respond to people in crisis. . All five battled alcohol use disorder, possibly self-medicating due to undiagnosed mental illness, she said.

Two are now dead. Two are in a shelter program where they receive alcohol as medication. The city tried to put one of them in conservatorship (mandatory treatment), but had to drop him when officials couldn’t find a location, Sloan said. The fifth is in a closed psychiatric facility.

In the city’s disjointed system, nonprofit organizations, police, paramedics, and public and private hospitals are responding to the crisis. But at the center of the system is the Department of Public Health, which is responsible for behavioral health treatment and runs the city’s only psychiatric emergency services department at San Francisco General Hospital. The city’s behavioral health budget for this fiscal year is $597 million.

Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, who called the hearing, questioned health department officials about whether the new programs are bringing relief to the overburdened department, and expressed skepticism that the programs would be effective without more dedicated resources for people in the most critical crises. sharp. Mandelman estimated that there were anywhere from several dozen to two hundred people who were “frequent flyers” cycling through the emergency room.

“I’m concerned about the psychiatric emergency because we need a center for people who need emergency psychiatric care, who we see too often without getting that care on the streets,” said Mandelman, a frequent critic of the health department and the health system. city. “I am deeply concerned about the direction the (health department) will take with regard to behavioral health facilities, if they have a clear plan to resolve the issues.”

The city passed legislation three years ago to overhaul the system. The pandemic has delayed implementation, but the city recently started more new programs to reduce the revolving door.

Dr. Hillary Kunins, director of the city’s behavioral health care system, told Mandelman she shares his “sense of urgency” and highlighted the progress the city has made in adding nearly 180 new treatment beds in the last two years.

“We intend to solve the problem of people in crisis, giving them the best possible opportunity for excellent care and linkage to ongoing services to prevent the next crisis,” he said. “Part of that is diverting an unnecessary (psychological emergency) admission.”

At the last count in 2019, there were 4,000 people in San Francisco struggling with homelessness, mental illness, and substance use.

The city’s only psychiatric emergency department limited its capacity to 19 beds at the start of the pandemic and still diverts all patients to its ER for COVID testing.

A third of patients are discharged directly from the emergency department, while two-thirds return, although in 18% of cases from February to June 2022, PES did not have space, officials said.

Before the pandemic, the PES was in “red condition,” diverting all patients to the emergency department, up to 30% of the time due to capacity, said Dr. Mark Leary, who presented on behalf of the hospital.

Hospital officials said they have “some staffing challenges for some positions” but were on track to fill two psychiatric emergency nurse vacancies.

Heather Bollinger, a union representative for SEIU Local 1021 and an emergency room nurse, said the problems have been widespread for years. She reported that nurses filled out more than 50 forms to report when they felt the department was violating staffing ratios in the past four months.

“I don’t think two RNs are enough to solve these kinds of working conditions,” Bollinger said.

Nurses and doctors complain that the staffing creates safety problems. Incidents of violence in the workplace hospital-wide they have risen steadily from fiscal year 2018, when they were 76, to 439 from June 2020 to July 2021, according to a health commission report. Emergency Room Dr. Scott Tchengwho spoke during public comment, said he doesn’t know anyone who works in the emergency department who hasn’t been punched, kicked or spat on.

The hospital agreed last year to reduce the number of sheriff’s deputies protecting facilities in response to protests from staff and advocates who denounced patient surveillance, but many emergency department workers have objected.

Meanwhile, connections to long-term care may be lacking. Leary said “there are still a small number of patients who return very frequently” to emergency departments, with most struggling with substance use disorder.

Leary said the city faces challenges in requiring treatment for those who refuse it. A new pilot program for people with severe substance use and mental illness was supposed to help up to 100 people, but only two people have been retained under the program in two years.

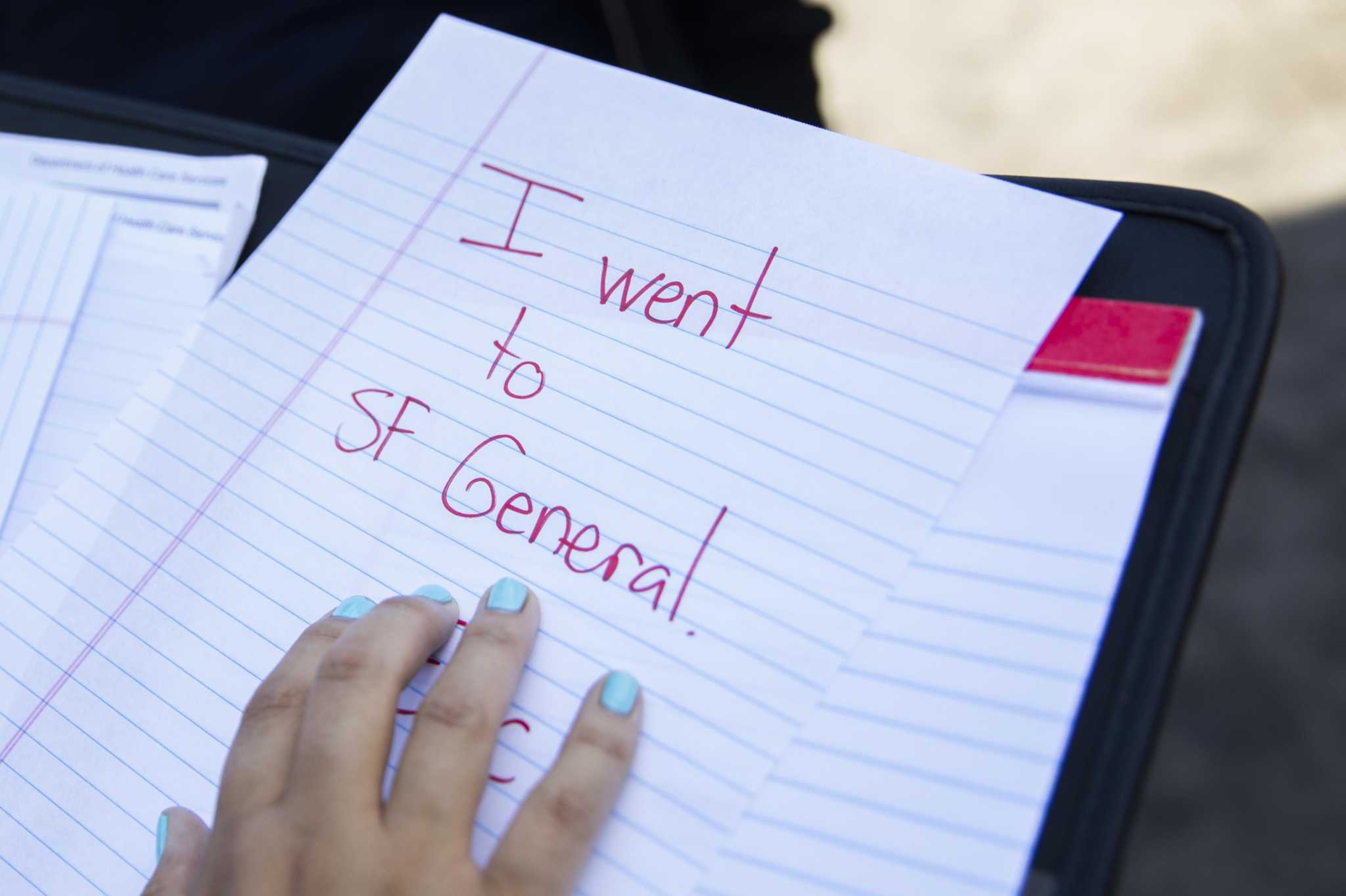

Of the people discharged from the psychiatric emergency, 65% received outpatient referrals, which most of the time was simply a piece of information paper. Officials said it probably wasn’t enough to get significant help, but it was one step in what would likely be many interactions to get someone to accept help.

Health department officials said they are working to improve links to treatment. Medications provided at discharge have increased 120% over the last year. The hospital recently established a new team to help coordinate care and has worked with nonprofits to reserve detox beds for discharged patients and expedite referrals to residential treatment.

Although San Francisco General is the only psychiatric emergency department in the city, data shows that private hospitals actually received more behavioral health patients from January 2021 to February 2022.

Dignity Health, which runs St. Mary’s and St. Francis, accounted for 30% of behavioral health ambulance traffic, with 29% going to Sutter Health, run by CPMC, followed by 19% going to San Francisco General.

To reduce the burden, the city has turned to a host of alternative programs, including a psychiatric urgent care clinic, Street Crisis Response Teams, and a drug sobriety center. The effectiveness of these programs in alleviating the burden of the psychological emergency is unclear or not yet known because they are too new.

The city plans to open another option, a 16-bed crisis diversion program, in late 2023, but who it will serve and how it will fit in with the other programs is still being determined.

The health department has opened 179 new treatment beds since the beginning of 2021 and another 70 are expected to open by the end of the summer. That puts the department more than halfway to its goal of 400 new placement beds. The city has also hired 411 behavioral health care workers since the beginning of the year, some of whom helped set up a new office to coordinate care.

Mallory Moench (she/her) is a staff writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @mallorymoench