Mia Flegal tells some high school students about her bouts of anxiety and depression and the toll mental illness can take on children and teens, when one student raises her hand to ask a heartbreaking question:

“What do I do if no one believes me?”

When children struggle with their mental well-being and mental health, it can look different than adults, and signs of distress can appear subtle or easy to dismiss.

Flegal, who just finished 10th grade at Nashua High School North, said he first experienced symptoms of his GAD when he was about 8 years old. He began to have trouble sleeping and began to notice that worry made it hard for him to breathe.

“It starts with this hole in the stomach,” Flegal said. “That hole in your stomach starts to creep up into your chest, and it feels like someone is squeezing you.”

He remembers waking up in a cold sweat when he was 10 years old on a trip away from home. Her mother, Sheelu Flegal, recalls that she picked her up early from a sleepover when Mia, usually outgoing and talkative, got caught up in her anxiety.

Her classmate at Nashua North, Aarika Roy, said she remembers her anxiety starting as stomachaches when she was in fifth grade.

Erin Murphy, now finishing 11th grade at Windham, recalled coming home from high school to find herself shaking, unable to stop crying and hyperventilating.

“It’s hard to tell if this is kind of a growth phase or if it’s turning into something,” Flegal said.

Even if it’s upsetting to think about elementary and middle school kids struggling with anxiety, depression or other mental illnesses, Flegal said, it happens. Being able to talk about bad feelings can help.

“It can’t be a top secret issue,” Flegal said.

The pandemic and the growing panic on social media have highlighted the enormity of the mental health challenges facing children and adolescents today.

According to a survey by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about one in three high school students reported poor mental health during the pandemic. Half said they felt persistently sad or hopeless. (cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/abes.htm)

Generation Z, born between 1997 and 2012, is gaining a reputation for being more open about mental health, but Flegal still isn’t sure her peers are comfortable talking about their mental health in a serious and honest way.

“A lot of what Gen Z does is joke about it. But making a joke about it is not the same as asking for help,” Flegal said. “If jokes are the first step, that’s fine, but ultimately we need to encourage people to seek help.”

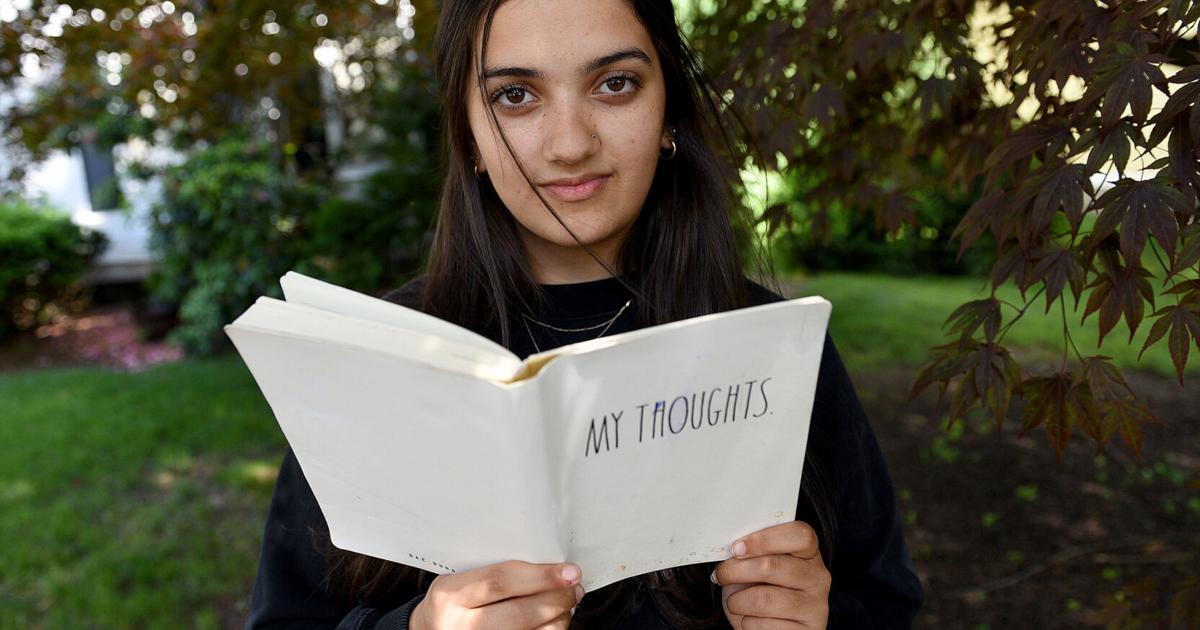

Mia Flegal at her home in Nashua on June 10, 2022. She has battled anxiety and now helps younger students with mental health issues.

help Wanted

More resources are coming online to deal with acute crises, like New Hampshire’s new “rapid response hotspot” for people who need help in a crisis, and the national crisis line, 988, which will be activated on 16 of July. And the state hopes to open more beds this fall at Hampstead Hospital, for children and teens who need more intensive care.

The state’s community mental health centers can connect people to treatment and make connections to help in other aspects of someone’s life.

Rik Cornell, vice president of community relations at the Greater Manchester Community Mental Health Centre, said the center has been able to place staff in almost every school in the city to work with students and train staff, and is providing similar help. in summer programs.

“For so many years, mental health has sat and waited for people to come to them. That’s not what we’re doing anymore,” Cornell said. “We can’t just keep picking up the pieces. We have to prevent these pieces from falling apart.”

Still, there are barriers to getting help.

When Flegal’s Nashua North classmate Aarika Roy had a severe anxiety attack two years ago, Roy said her family tried to call therapists throughout New Hampshire and Massachusetts for most of the two years, but never got around to it. they were able to get an appointment. with a psychologist.

Cornell said there is a serious and growing shortage of psychologists, therapists and all sorts of other health workers, but said families with a lot of money have an easier time getting therapy and other mental health care.

Many therapists are reluctant to accept health insurance because it can be difficult to persuade insurance companies to pay for their services. Cornell said some therapists are accepting new patients, as long as those patients can pay cash.

But Cornell said New Hampshire’s 10 community mental health centers (nhcbha.org) can help people who find they can’t access mental health care.

“Call us,” Cornell said. “We’ll see what we can do to get you in.”

dealing on your own

Unable to see a therapist, Roy said he found other ways to deal with his anxiety: leaning on his family’s Hindu spirituality and even looking up YouTube videos on breathing and meditation.

Flegal said she, too, has found ways to cope.

She began journaling after bouts of anxiety, analyzing her thoughts. In the middle of an attack, when she is caught in a cycle of hyperventilating and crying, she counts her breaths, or she takes a couple of ice cubes and squeezes them to “shock” her body out of the cycle.

Those coping mechanisms have evolved over the years, Flegal said, but she said having people to talk to — her family, her friends, trusted teachers — helps her stay on top of things.

However, during the pandemic, Flegal said, much of that support network disappeared, an experience shared by many children and adults.

Isolated from her friends, with limited chances to interact with teachers as Nashua remained in remote learning for much of the 2020-21 school year, Flegal said she would get out of bed a few minutes before a Zoom class and sit taciturn in front of her computer. with the camera off. When she got out of class, she would get in the shower, put on some music and cry.

“I was stuck in a hole,” she said. “She didn’t see the end of it, and it’s very difficult.” She was worried about asking for help, she was worried about being a burden on her family or increasing tensions in the home.

But when she recognized those feelings of hopelessness, Flegal said, her family listened, cared and helped.

“Seeking help doesn’t make you weak and it doesn’t have a negative effect on those around you,” he said.

feel less alone

Family members, teachers, coaches — anyone who gets to know a child or teen well — can watch for changes in behavior and ask about them, like changes in sleep or hygiene, Diana Schryver said. , clinical coordinator for the children’s department at the Greater Manchester Center for Mental Health.

Adults can ask behavioral questions first, gently, and then open up a conversation for a young person to talk about their emotions and mental well-being.

“One of the things we talk about helping people do is develop their awareness skills,” Schryver said. “It may not be a crisis, but it could be a construction crisis.”

Murphy, the Windham student, remembers being pulled aside one day by an eighth-grade teacher, when she came to school in pajamas and with matted hair, to ask how she was doing. That conversation gave Murphy the space to admit for the first time that she wasn’t doing well.

“He asked me if you were okay and the answer was no,” Murphy said.

She is grateful that the teacher made the effort to verify.

Feeling safe to talk about feelings, especially difficult feelings, is important even for the youngest children. Flegal said he has been working with community groups to develop programs where he can talk to younger people, talk about his mental health history and try to help other kids feel comfortable talking about their own feelings.

Flegal said she is open about her struggle with mental health because she wants other people, especially younger children, to see that it’s safe to talk about her mental health. To that girl who asked what to do if no one believed her about her struggle with mental health, Flegal told her to keep talking.

Schryver said the same thing.

“To that young man I would say, don’t stop talking. Don’t stop asking for help until you feel like you’re getting the help you need.”

.