You are probably underestimating your muscles. In fact, almost everyone does. Although everyone knows, for example, that muscles are important for function-activities such as walking, climbing, and lifting—few appreciate how important muscles are to feeling.

If you haven’t noticed this connection between mood and muscles yourself, take heart; it’s just a recent discovery. Surprisingly, the entire scientific community remained in the dark until about 2003 (1), when a Copenhagen-based team of researchers reported a remarkable discovery: Working muscles secrete tiny chemical messengers called myokines that exert powerful effects on muscle function. of organs, including brain function (2).

Through the actions of myokines, muscle tissue communicates directly with the brain about its activity, triggering a cascade of biological responses that enhance memory, learning, and mood (see Figure 1 below). This recently discovered mechanism implies that a person who engages in physical activities that build and maintain healthy muscle tissue can expect to enjoy a variety of cognitive and mental health benefits. Recent clinical trials show precisely this effect (3).

Source: Thomas Rutledge

If anyone has ever accused you of being complicated, I really had no idea. Although you can’t tell by looking in the mirror, the body you see reflected is made up of more than 100 trillion cells. The cells are tiny; if you put cells next to each other in a police row, for example, about 200 of them would fit in a single millimeter.

But that’s just the beginning of the miracle we call you. Every cell in his body is a thriving civilization unto itself, populated by hundreds of millions of proteins and other molecules, each possessing a work ethic that would put John Henry in awe. shame. On a scale of our size, its cellular citizens fly at the speed of fighter jets, each of which is busy completing hundreds or even thousands of vital functions per second. They must keep up this frenetic pace without interruption for you to survive, totaling billions of trillions of precisely performed chemical activities every day.

If you somehow possess a superhuman imagination able to conceive of this cellular cacophony, one question may arise: what powers all this? Surprisingly, the enormous energy required to run your cells ultimately comes from the oxygen you breathe and the food you eat.

The latter seems important to remember the next time you don’t feel like eating vegetables. Digested to the lowest denominator, the mitochondria, possibly the VIP citizens of your cells, convert the nutrients into billions of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules per minute. Although even an ordinary cell can house thousands of these energy-producing mitochondria, muscle cells are mitochondrial hives, possessing tens or even hundreds of thousands to power their operations. Once done, your cells feast on ATP like exhausted runners gobbling up PowerBars at the Boston Marathon finish line.

Emerging almost impossibly from this molecular chaos is you. Every thought, feeling, and action results from and depends on this never-ending cycle of energy demand and production. And if it’s not obvious from this description, the better your cells function at the small level, the better you’ll feel and function at the big level.

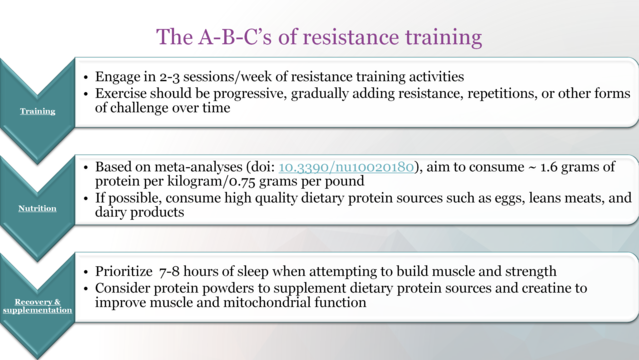

This brings us back to resistance training. Given the vital roles your muscles play in energy production and brain function, perhaps it’s time to start appreciating resistance training and muscle building as useful to more than athletes and magazine models.

Using muscles against resistance, for example, is much more effective at strengthening bones than any calcium supplement (4). Regular muscle activity also improves insulin resistance (the cause of diabetes and many other metabolic conditions) better than any prescription drug.

And we now know that stimulating muscle tissue with resistance training has emotional effects that rival those of conventional training. antidepressants and psychotherapies (3). Recent neuroscience suggests that we develop brains for one main reason: to move (5). Contrary to our traditional preoccupation with thought, the main function of the human brain is to coordinate complex movement (which is probably why we have brains while giant but stationary sequoias do not).

By recognizing this intimate connection between brain and movement, the biological basis of the mind-muscle relationship becomes clear and the importance of resistance training for optimal physical and emotional health becomes indisputable.

Source: Thomas Rutledge