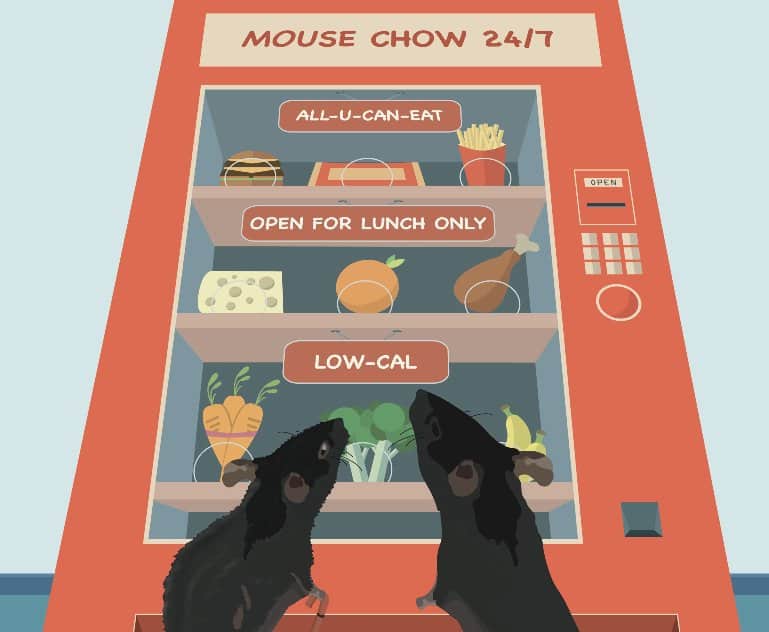

Resume: Restricting calories and eating only during the busiest part of the day helped extend the lifespan of the mice.

Source: HHMI

A recipe for longevity is simple, if not easy to follow: eat less. Studies in a variety of animals have shown that restricting calories can lead to a longer, healthier life.

Now, new research suggests that the body’s daily rhythms play a role in this longevity effect. Eating only during their busiest time of day substantially extended the lifespan of mice on a low-calorie diet, Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator Joseph Takahashi and his colleagues report May 5, 2022, in the journal Science.

In his team’s study of hundreds of mice over four years, a low-calorie diet alone extended the animals’ lives by 10 percent. But feeding the mice the diet only at night, when the mice are most active, prolonged lifespan by 35 percent. That combo — a low-calorie diet plus a nightly feeding schedule — added an extra nine months to the animals’ typical two-year average lifespan. For people, an analogous plan would restrict eating to daylight hours.

The research helps unravel the controversy surrounding diet plans that emphasize eating only at certain times of the day, says Takahashi, a molecular biologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Such plans may not accelerate weight loss in humans, as a recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine they reported, but could lead to health benefits that add up to a longer lifespan.

Takahashi’s team’s findings highlight the crucial role of metabolism in aging, says Sai Krupa Das, a nutrition scientist at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging who was not involved in the work. “This is a very promising and landmark study,” she says.

fountain of youth

Decades of research have found that calorie restriction extends the lifespan of animals ranging from worms and flies to mice, rats, and primates. Those experiments report weight loss, better glucose regulation, lower blood pressure, and reduced inflammation.

But it has been difficult to systematically study calorie restriction in people who cannot live in a laboratory and eat measured portions of food throughout their lives, says Das. He was part of the research team that conducted the first controlled study of caloric restriction in humans, called the Comprehensive Assessment of the Long-Term Effects of Reducing Energy Intake, or CALERIE. In that study, even a modest reduction in calories “was remarkably beneficial” in reducing signs of aging, Das says.

Scientists are just beginning to understand how caloric restriction slows aging at the cellular and genetic levels. As an animal ages, genes related to inflammation tend to become more active, while genes that help regulate metabolism become less active. Takahashi’s new study found that calorie restriction, especially when timed with the mice’s active period at night, helped offset these genetic changes as the mice aged.

matter of time

Recent years have seen the rise of many popular diet plans that focus on what’s known as intermittent fasting, such as fasting every other day or eating only for a period of six to eight hours per day. To tease out the effects of calories, fasting, and daily or circadian rhythms on longevity, Takahashi’s team conducted an extensive four-year experiment. The team housed hundreds of mice with automatic feeders to control when and how much each mouse ate throughout its life.

Some of the mice could eat as much as they wanted, while others were restricted in calories by 30 to 40 percent. And those on calorie-restricted diets ate at different times. Mice fed the low-calorie diet at night, for either a two-hour period or a 12-hour period, lived longer, the team found.

The results suggest that time-restricted eating has positive effects on the body, even if it does not promote weight loss, since New England Journal of Medicine suggested study. Takahashi notes that his study also found no differences in body weight between the mice at different feeding times, “however, we did find profound differences in life expectancy,” she says.

Rafael de Cabo, a researcher in gerontology at the National Institute on Aging in Baltimore, says that Science paper “is a very elegant demonstration that even if you are restricting your calories but you are not [eating at the right times]you don’t get all the benefits of calorie restriction.”

Takahashi hopes that learning how calorie restriction affects the body’s internal clocks as we age will help scientists find new ways to extend healthy lifespans in humans. That could come from calorie-restricted diets or medications that mimic the effects of those diets.

Meanwhile, Takahashi is learning a lesson from his mice: he restricts their feeding to a 12-hour window. But, she says, “if we find a drug that can speed up your clock, we can test it in the lab and see if it extends lifespan.”

About this longevity research news

Author: press office

Source: HHMI

Contact: Press Office – HHMI

Image: The image is attributed to Fernando Augusto

original research: Closed access.

“Circadian Alignment of Early-Onset Caloric Restriction Promotes Longevity in Male C57BL/6J Mice” by Victoria Acosta-Rodríguez et al. Science

Resume

Circadian Alignment of Early-Onset Caloric Restriction Promotes Longevity in Male C57BL/6J Mice

Calorie restriction (CR) prolongs life expectancy, but the mechanisms by which it does so remain poorly understood. Under CR, mice self-impose chronic cycles of 2-hour feeding and 22-hour fasting, raising the question of whether calories, fasting, or time of day are causal. We show that 30%-CR is enough to extend the useful life 10%; however, a daily fasting interval and circadian alignment of feeding act together to extend lifespan by 35% in male C57BL/6J mice.

These effects are independent of body weight. Aging induces systemic increases in the expression of genes associated with inflammation and decreases in the expression of genes encoding components of metabolic pathways in the liver from at will fed mice. CR at night improves these aging-related changes.

Therefore, circadian interventions promote longevity and provide a perspective to further explore the mechanisms of aging.