The GDD is a collaborative effort to systematically identify, compile, and standardize individual-level dietary data on 53 foods, beverages, and nutrients (Methods). The GDD uses Bayesian modeling methods to estimate dietary intake jointly stratified by age, sex, education, level, and urbanization for 185 countries between 1990 and 2018.

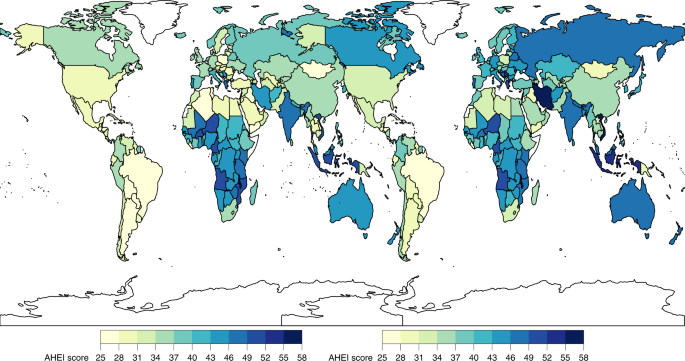

Global and regional diet quality in 2018

In 2018, the global mean AHEI score was 40.3 (95% uncertainty interval (IU) 39.4, 41.3), with regional means ranging from 30.3 (28.7, 32, 2) in Latin America and the Caribbean to 45.7 (43.8, 49.3) in Latin America and the Caribbean. South Asia (Fig. 1). Among the score components, the highest overall scores for the healthiest items were legumes/nuts (5.0, 4.8, 5.3), followed by whole grains (4.7, 4.5, 5.0 ), omega-3 fats from seafood (4.2, 3.8, 5.1), and non-starchy vegetables (3.9, 3.8, 4.0); among the least healthy items, the highest scores (lowest or most favorable consumption) were for sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) (5.8; 5.7, 5.9) and red/processed meat (4.8; 4.5, 5.1). However, these score components varied substantially by world region. For example, the highest scores in South Asia were for more whole grains and less red/processed meat and SSB, while the highest scores in Latin America and the Caribbean were for more legumes/nuts. and less sodium.

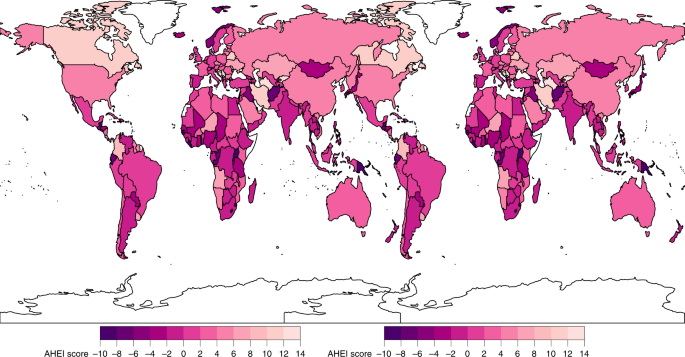

Quality of the national diet in 2018

Only ten countries, representing <1% of the world population, had AHEI scores ≥50. Among the 25 most populous countries in the world, the average AHEI score was highest in Vietnam, Iran, Indonesia, and India (54.5 to 48.2) and lowest in Brazil, Mexico, the United States, and Egypt (27.1–33.5) (Fig. two). Most component scores varied substantially across these populated countries. For example, a 100-fold difference in sodium score, a 90-fold difference in red/processed meat score, and a 23-fold difference in SSB score were observed. Among components, polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) and non-starchy vegetable scores varied less (two- and three-fold, respectively) between populated countries.

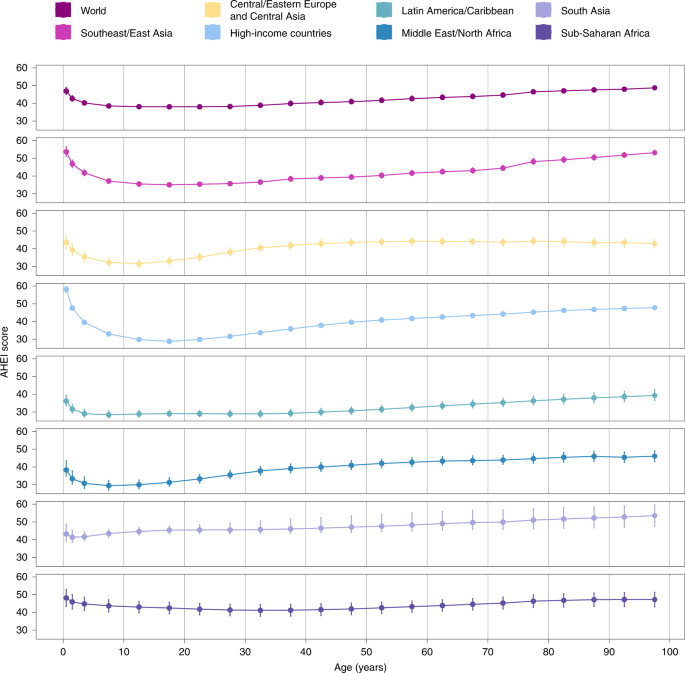

Global and regional differences between demographic subgroups

Globally, the mean AHEI score in 2018 was similar among children (39.2, 38.2, 40.3) versus adults (40.8, 39.8, 42.0) (Fig. 1). However, the mean AHEI score was substantially higher among adults compared to children in Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, high-income countries, and the Middle East and North Africa region. By age, most regions had J- or U-shaped relationships, with the highest scores observed among the younger (≤ 5 years) and/or older (≥ 75 years) age groups (Fig. 3).

The AHEI score ranged from 0 to 100. The circles represent the global or regional mean for the age group and the error bars represent the corresponding 95% UI. The mean and its IU are plotted for the midpoint of each age group (<1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30– 34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, 90–94 and ≥95 years).

Among AHEI components globally, scores for four components were lower among children than adults: fruits (2.2 (2.1, 2.3) vs. 2.5 (2.4, 2 .5), respectively), non-starchy vegetables (3.1 (3.0, 4.5) vs. 4.3 (4.2, 3.2)), SSB (5.3 (5.1, 5.5) vs. 6.1 (6.0, 6.2)) and omega-3 from shellfish (3.3 (2.9, 4.0) versus 4.7 (4.2, 5.7)), while two others were higher among children versus adults: PUFA (2.1 (2.0, 2, 2) vs. 1.4 (1.3, 1.5)) and sodium (4.6 (4.1, 5.1) vs. 3.2 (2.9, 3.5)) (Fig. 1).

By gender, the mean AHEI score was generally higher in women than in men at the global and regional levels, with the largest differences observed in high-income countries (+4.4 difference, 3.8, 5, 0) and Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia (+3.6; 2.1, 5.3) (Extended Data Fig. 1). When evaluating different components of the AHEI globally, women scored moderately higher for fruits (+0.2, 0.2, 0.3), non-starchy vegetables (+0.3, 0.1, 0.4 ) and whole grains (+0.4; 0.2, 0.5).

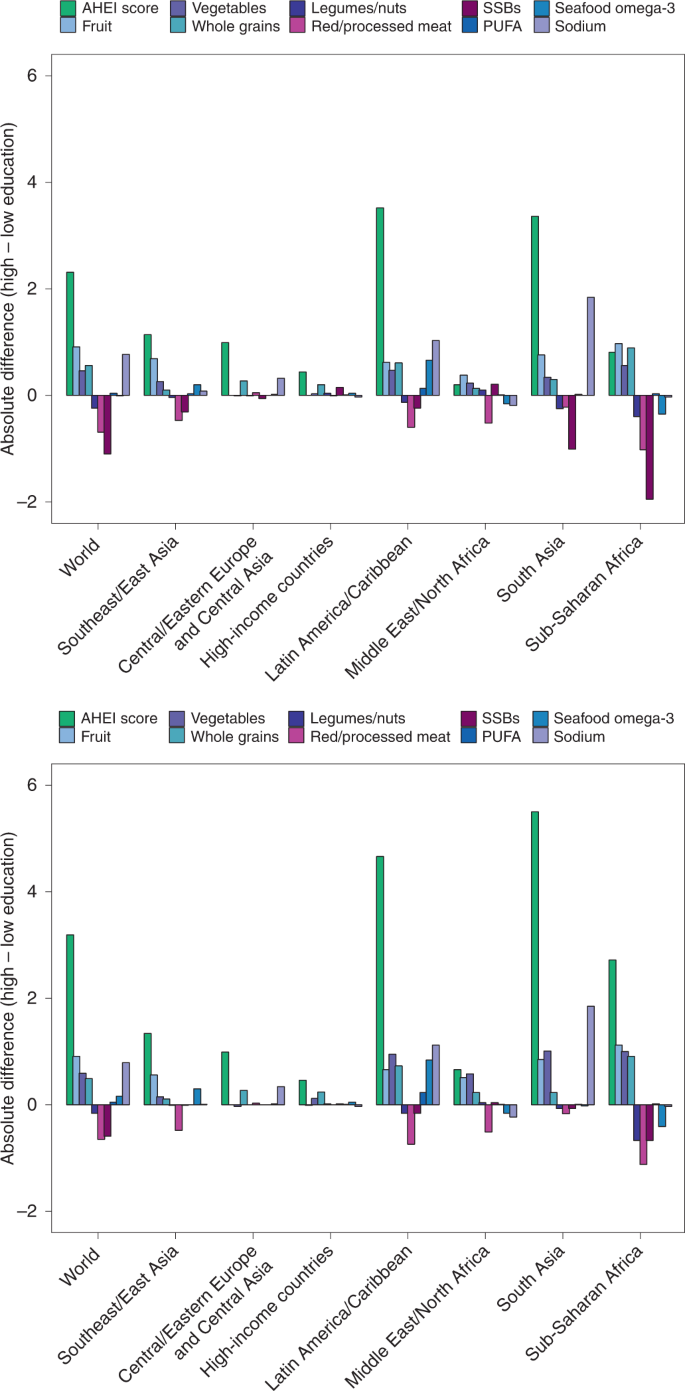

Assessing for differences by educational level, AHEI scores were higher among the more highly educated globally and in most regions except the Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa, where they were not observed. differences (Fig. 4). Among world regions, differences by education were largest in Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia (+3.6, 2.4, 4.9), Latin America and the Caribbean (+3.5, 0.9, 6.0) and South Asia (+2.9; 1.1, 4.9) . Globally, more educated people scored higher for fruits (+0.8; 0.7, 0.9), sodium (+0.7; 0.3, 1.1), whole grains (+0.6; 0.4, 0.8), and non-starchy vegetables (+0.5 ; 0.4, 0.6). However, in contrast, more educated people also had lower scores (less favorable consumption levels) for red/processed meat (−0.6, −0.7, −0.5), SSB (−0.6, −0.8, −0.4), and nuts and legumes (−0.1, −0.2, −0.1) globally.

AHEI score: nine components scored from 0 to 10 each and scaled to ten components (correction not shown). The absolute difference by education was calculated as the difference at the stratum level and added to the global and regional mean differences using weighted population proportions for low (<6 years) and high (≥12 years) education levels only (excludes of education ≥6 years). and <12 years).

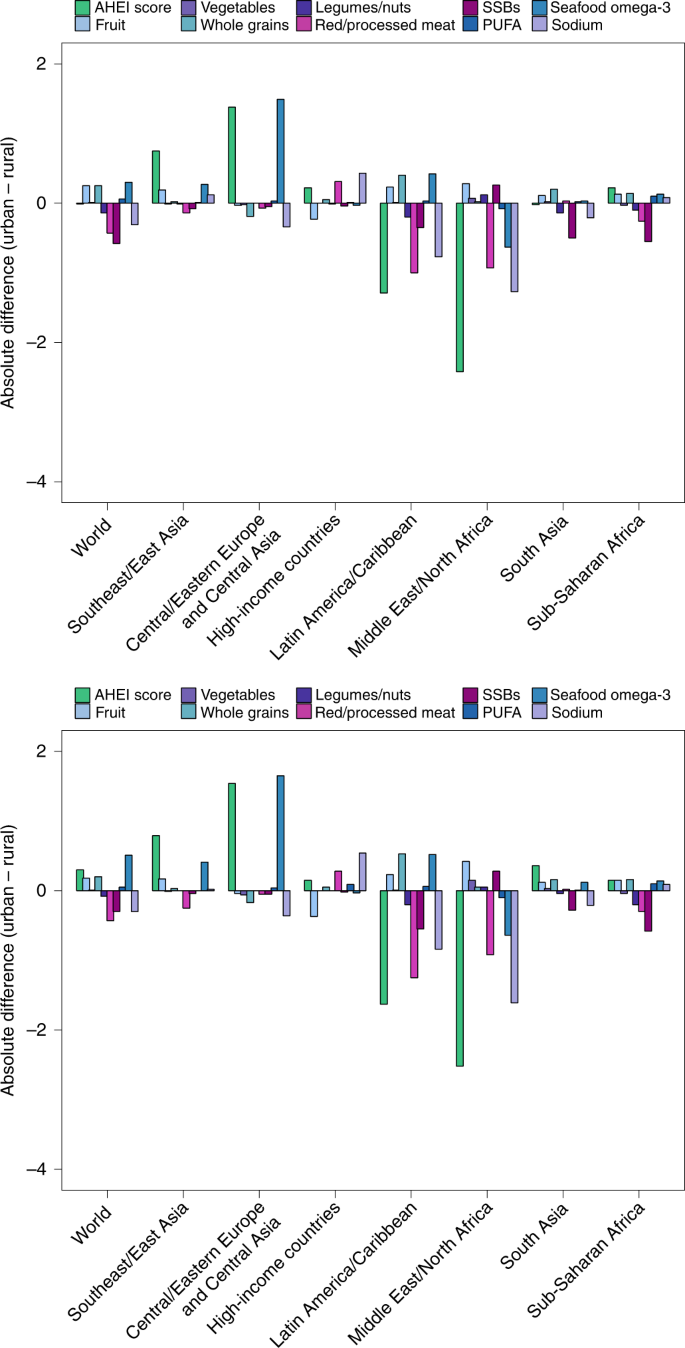

Overall, AHEI scores did not vary significantly by urban versus rural residence (Fig. 5). However, higher scores were evident among urban versus rural people in Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia (difference +2.2, 0.9, 3.5), and Southeast and East Asia (+ 1.4, 0.6, 2.4), and lower scores among urban versus rural people. individuals in the Middle East and North Africa (−3.8; −5.5, −2.2). Globally, people residing in urban areas had higher scores for fruits (+0.2, 0.2, 0.3) and whole grains (+0.2, 0.1, 0.4), but lower scores for SSB (−0.5, −0.7, −0.4), red/processed meat (−0.4, −0.5, −0.1), and legumes/nuts (−0.1, −0.2, −0.1).

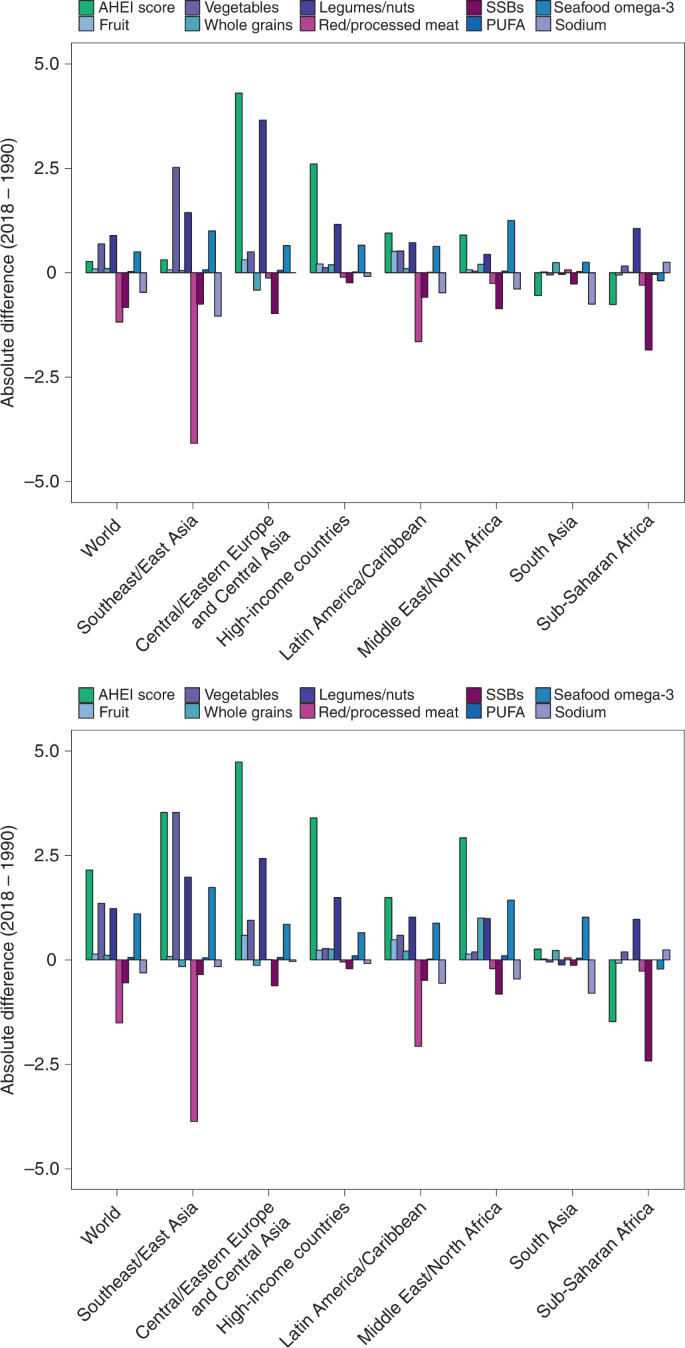

Changes in dietary pattern scores between 1990 and 2018

Between 1990 and 2018, the average global AHEI score (standardized to 2018 population distributions) increased by +1.5 (1.0, 2.0). Increasing trends occurred in five of seven regions: Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia (+4.6, 4.0, 5.3); high-income countries (+3.2, 2.9, 3.5); Southeast and East Asia (+2.7; 1.7, 3.8); Middle East and North Africa (+2.2; 1.4, 3.0); and Latin America and the Caribbean (+1.3; 0.6, 2.0). No significant change was observed in South Asia (0, −0.9, 1.1) and a decreasing trend was observed in sub-Saharan Africa (−1.1, −1.8, −0.4) (Fig. . 6).

Among AHEI components globally, scores increased over time for non-starchy vegetables (+1.1, 1.0, 1.2), legumes/nuts (+1.1, 1.0, 1, 3) and fruits (+0.1; 0.1, 0.2); decreased for red/processed meat (−1.4, −1.5, −1.2), SSB (−0.6, −0.7, −0.6), and sodium (−0.4, −0.6, −0.2); and remained stable for whole grains (+0.1, 0, 0.2), PUFA (0, 0, 0.1), and omega-3 fish and shellfish (0, 0, 0.1).

Among the most populous countries, the largest absolute improvement in AHEI score between 1990 and 2018 occurred in Iran (+12.0; 9.9, 13.9), the United States (+4.6; 4.1, 5.1), Vietnam (+4.5; 2.4, 7.2) and China (+4.3; 2.8, 5.9), while the largest decreases were found in Tanzania (−3.7; −5.8, −1.5), Nigeria (−3.0; −5.3, −0.7), Japan (−2.7; −3.1 , −2.3) and the Philippines (−1.8; −2.7, −0.9) (Fig. 7).

Results for DASH and MED

Detailed results of the DASH and MED scores are presented in supplementary information. Briefly, the global mean DASH and MED scores in 2018 were 22.9 (22.6, 23.2) and 4.1 (3.9, 4.2), respectively (extended data, Figs. two Y 3). At the regional level, the averages of these scores were consistently higher in South Asia and lower in Latin America and the Caribbean (extended data, Figs. 4 Y 5). Among population subgroups, global DASH and MED scores were higher among adults than children (DASH: 23.2 (22.9, 23.4) vs 22.3 (21.9, 22.7). ); MED: 4.3 (4.1, 4.4) vs. 3.7 (3.5, 3.8)), but did not differ appreciably by sex (Extended Data Figs. two Y 3). The global mean scores were higher among individuals with a higher educational level compared to those with less education (difference +2.6 (2.3, 2.8) and +0.3 (0.2, 0.4), respectively). ) (Extended data Fig. 7) and, only for DASH, between urban versus rural individuals (+0.4; 0.2, 0.7) (Extended Data Fig. 8). Worldwide, mean DASH and MED scores increased modestly between 1990 and 2018, +1.0 (0.8, 1.1) for DASH and +0.3 (0.2, 0.4) for MED (extended data Figs. 6 Y 9). Across all strata in 2018, dietary pattern score intercorrelations were 0.8 for AHEI and DASH, 0.5 for AHEI and MED, and 0.6 for DASH and MED.