Australian health professional Ariane Beeston has written a book about her experience with postpartum psychosis.

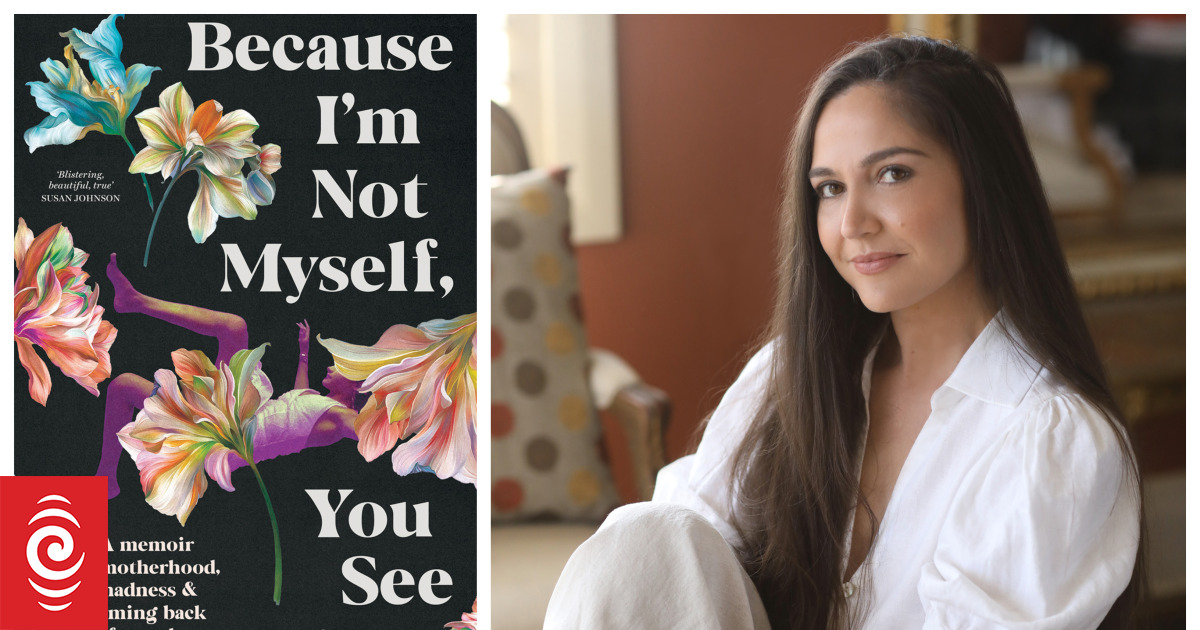

Photo: supplied by Black Inc Books

Ariane Beeston was walking her son in his stroller when she looked down and didn’t see a baby.

“I was walking home from work, pushing the stroller, and Henry had turned into a dragon. He was hallucinating. At the time, it was actually more of a return of those psychotic symptoms that he had experienced those hallucinations when he was much younger,” he tells Nine to Noon’s Katherine Ryan.

“I had gone back to work, I had convinced my psychiatrist that going back to work would be good for my recovery, that it would help me feel more competent and help me feel like myself again.

“…it was a real relapse, a real wake-up call that I was not really recovered, I was not well.

“I had this really strange feeling that my hands and fingers didn’t belong to me, just a very, very distressing, almost disembodied feeling.”

Beeston was in her 20s and working as a psychologist in the New South Wales Department of Communities and Justice when she took time off to have her first child.

“[It was] Very, very stressful and intense work… it sort of laid some of the foundation for what happened to me after childbirth in terms of my psychotic illness… there were elements of particular cases that I had worked on that appeared later ”.

Beeston has written a book about her experience of postpartum psychosis, Because I’m not myself, you see..

Beeston’s career began on the child protection health line in Australia, fielding calls from nurses, doctors and teachers, as well as community members, about children at risk of harm. She later became a frontline social worker: she investigated cases and, if necessary, removed children from unsafe environments.

Her book begins with a story about diaper rash. It’s not unusual in babies, but for Beeston it’s a real trigger.

“I made the link that I had been involved in taking the children into care; sometimes they had diaper rash, sometimes they had lice, and that particular characteristic stuck in my mind and I became convinced that the department would come to remove my baby because of the diaper rash,” she says.

Postpartum psychosis affects 1 or 2 in every 1,000 new mothers in Australia, and each experience is unique, Beeston says. That equates to about 600 women a year in Australia. It should be considered a psychiatric emergency, but it is not always detected. Symptoms can be subtle, as was the case with Beeston.

“I was a mental health professional and suffered from mental illness, so that was an extra layer of stigma for me.

“I was worried that if I was too honest about how bad things are, would that mean they would take my registration away? What won’t I be able to practice? What will my colleagues think of me? Will I be able to work again?

While Beeston’s experience was extreme, her book sheds light on the variety of conditions women can experience after childbirth.

“Many of us wait for that wave of love, that love at first sight, that cinematic moment. And it can be really distressing when women hold their baby for the first time and don’t feel that,” she says.

“There’s this expectation that motherhood is going to be natural, that it’s instinctive… and if you don’t feel that then, you’re failing.”

Many women experience chronic insomnia, breastfeeding problems, and relationship changes. And almost all women will have “intrusive thoughts,” she says.

“Almost all women, between 80 and 100 percent of women, will experience an intrusive thought that something will happen to their baby.” They are things like tripping down the stairs and falling with the baby in your arms or being on a balcony and the baby falls.

And 50 percent of women will experience intrusive thoughts of intentionally harming their baby.

“For these women it is horrible, it is distressing, they have these thoughts and they don’t understand why. “There is no evidence that having these thoughts is related to carrying them out.”

Beeston completed two stints in a mother-baby unit at a psychiatric hospital in New South Wales, where therapy, medication and targeted perinatal support helped her heal.

“It takes time to… process, to process the enormity of what happened… to process the pain of the time I felt I had lost by being so unwell and also the development of my relationship with my baby.

“Once that love came about, I felt completely in love…falling in love with him, with my baby, really helped me get through recovery.”