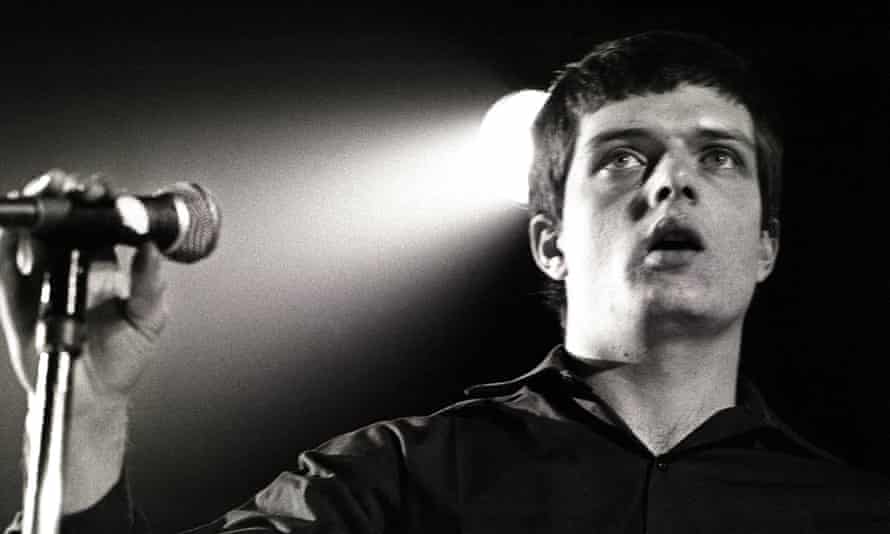

The lead singer of New order has attacked “ridiculous” NHS waiting lists for mental health support, as he spoke about his heartbreak at being unable to help his former bandmate Ian Curtis in the days before he took his own life 42 years ago.

Speaking at a suicide prevention event in Parliament, Bernard Sumner, who was a member of the post-punk band joy divisionwhose lead singer, Curtis, committed suicide at his home in Macclesfield on May 18, 1980, described the suicide of a friend’s daughter who had been told she would have to wait 18 months for help.

“You can’t go on a waiting list if you’re thinking about killing yourself. It’s ridiculous,” Sumner said. “You can’t wait 18 months. You need help immediately.”

There are 1.6 million people in National Health Service waiting lists for mental health services, and health leaders estimate that another 8 million cannot get help from specialists because they are not considered sick enough to qualify.

Sumner spoke alongside Labor leader Keir Starmer and a health minister, Gillian Keegan, at an event exploring how suicide rates could be reduced. It was introduced by Lindsay Hoyle, the Speaker of the House of Commonswho was on the verge of tears when he spoke about his daughter’s suicide.

“We know there are massive waiting lists,” said Keegan, who also spoke about how he had lost a younger cousin to suicide. “I worry about it every day.”

She said the government was working to train 27,000 more mental health professionals and provide more mental health support in schools and suicide prevention policies that particularly target high-risk groups, including men aged 45 to 55 year olds, new mothers and people leaving the military.

Suicide rates in England and Wales have been stable in recent years at between 10 and 11 deaths per 100,000 people, according to deaths recorded by coroners following investigations into unexpected deaths. In 2020, 5,224 suicides were recorded, three quarters of which were men. The suicide rate is markedly lower now than it was in the early 1980s when Curtis died, when there were about 14 suicides per 100,000 people.

Sumner described how Curtis stayed with him for a fortnight before he died in 1980.

“Every night I tried to talk him out of it,” Sumner said. “He agreed with me, but he was on a mission. It was going to happen. I don’t know what else we could have done.”

At just 23 years old, Curtis was married with a young daughter, but their marriage was headed for divorce. He had depression and epilepsy and had made a previous attempt to take his own life.

Sumner called on mental health professionals who are helping people at risk of suicide to start reaching out to their families who may not know about the issues, in a challenge to current patient confidentiality rules.

Keegan responded, “It’s not easy because of the age of consent, and if someone doesn’t want you to be involved, more family involvement will help in many cases.”