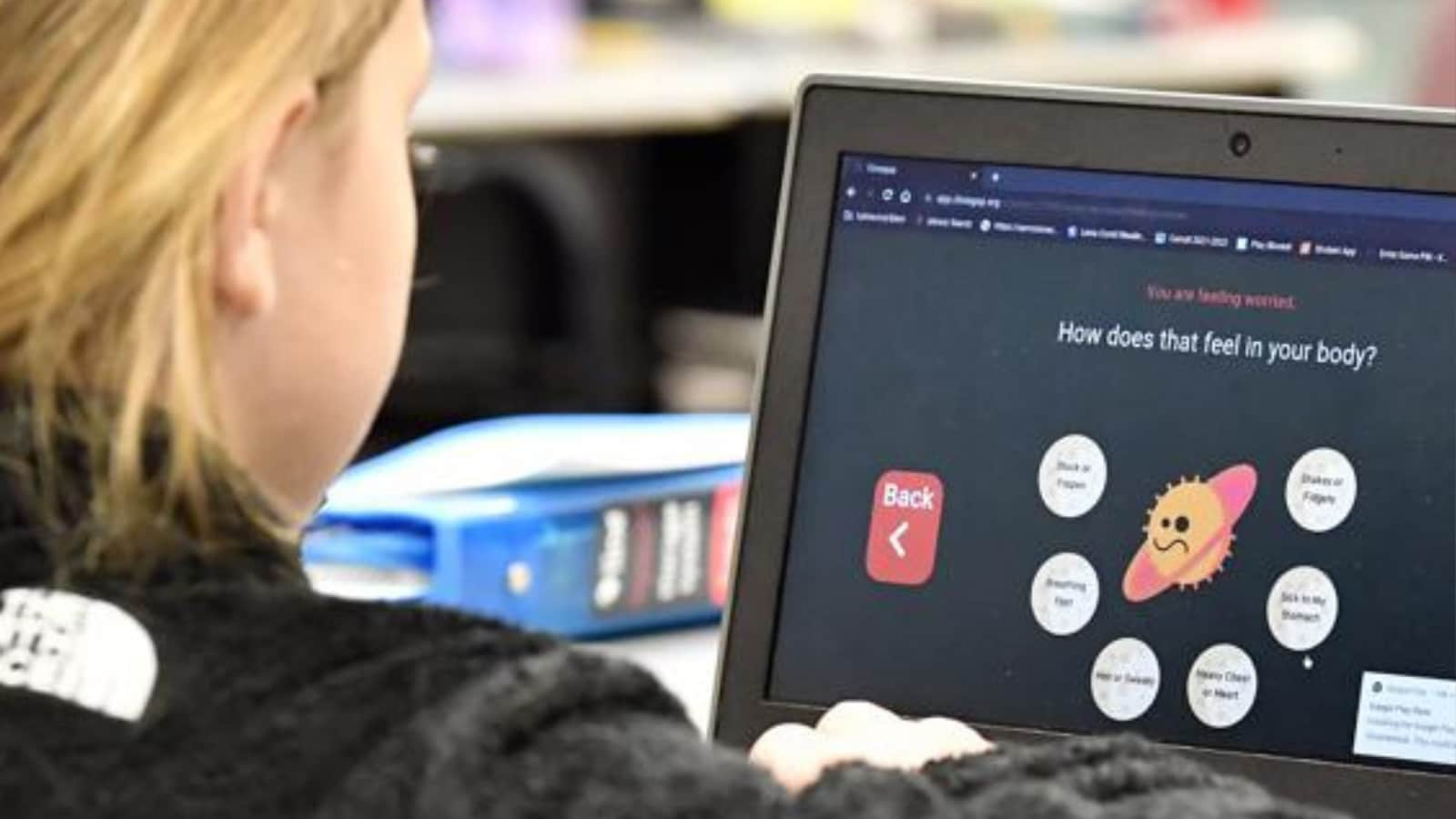

For fourth grader Leah Rainey, the school day now begins with what her teacher calls an “emotional check-in.”

“It’s great to see you. How are you feeling?” she chirps a cheerful voice into his laptop screen. She asks you to click on an emoji that matches her mood: happy. Sad. Concerned. Pissed off. Frustrated. Calm. Fool. Tired.

Depending on the answer, 9-year-old Leah gets advice from a cartoon avatar on how to manage her mood and a few more questions: Have you had breakfast? Are you injured or sick? Is everything okay at home? Is someone at school being rude? Today, Leah chooses “silly,” but she says that she struggled with sadness during online learning.

At Lakewood Elementary School, all 420 students will start their days the same way this year. The rural Kentucky school is one of thousands across the country using technology to gauge student mood and alert teachers to any difficulties.

In some ways, this year’s back-to-school season will restore a degree of pre-pandemic normalcy: Most districts have lifted mask mandates, dropped COVID vaccination requirements, and scrapped rules on social distancing and quarantines.

But many of the pandemic’s most lasting impacts remain a worrying reality for schools. Among them: the harmful effects of isolation and remote learning on children’s emotional well-being.

Student mental health reached crisis levels last year, and the pressure on schools to find solutions has never been greater. Districts across the country are using federal pandemic money to hire more mental health specialists, implement new coping tools and expand curriculum that prioritizes emotional health.

Still, some parents don’t think schools should be involved in mental health at all. So-called social-emotional learning, or SEL, has become the latest political flashpoint, with conservatives saying schools use it to promote progressive ideas about race, gender and sexuality, or that a focus on wellness deflects attention of academics.

But at schools like Lakewood, educators say helping students manage emotions and stress will benefit them in the classroom and throughout their lives.

The school, in a farming community an hour’s drive south of Louisville, has used federal money to create “take a break” corners in each classroom. Students can check out a “self-regulation kit” with tips on deep breathing, soft stress balls and acupuncture rings, said school counselor Shelly Kerr. The school plans to build a “Reset Room” this fall, part of an emerging national trend to create campus sanctuaries where students can relax and talk with a counselor.

Lakewood’s online student screener, called Closegap, helps teachers identify shy, quiet kids who might need to speak up and might otherwise have gone unnoticed.

Closegap founder Rachel Miller launched the online platform in 2019 with a few schools and saw interest explode after the pandemic hit. This year, she said, more than 3,600 US schools will use the technology, which has free and premium versions.

“We are finally beginning to recognize that school is about more than just teaching children to read, write and do arithmetic,” said Dan Domenech, executive director of the National Association of School Superintendents. Just as free lunch programs are based on the idea that a hungry child can’t learn, more and more schools are embracing the idea that a disordered or troubled mind can’t focus on schoolwork, he said.

The pandemic magnified the fragility of mental health among young Americans, who had been experiencing rising depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts for years, experts say. A recent report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 44% of high school students said they experienced “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” during the pandemic, with LGBTQ girls and youth reporting higher levels. higher rates of mental health problems and suicide attempts. .

If there is a silver lining, the pandemic has raised awareness of the crisis and helped de-stigmatize talking about mental health, while drawing attention to the shortcomings of schools in managing it. The administration of President Joe Biden recently announced more than $500 million to expand mental health services in the nation’s schools, adding to federal and state money that has been poured into schools to address the needs of the pandemic era.

Still, many are skeptical. The responses from the schools are sufficient.

“All of these opportunities and resources are temporary,” said Claire Chi, a junior who attends State College Area High School in central Pennsylvania. Last year, her school added therapy dogs and emergency counseling, among other supports, but most of that help lasted a day or two, Chi said. And that “is not really an investment in mental health for students.” This year, the school says it has added more counselors and plans mental health training for all 10th graders.

Some critics, including many conservative parents, don’t want to see support for mental health in schools in the first place. Asra Nomani, a parent from Fairfax County, Virginia, says schools are using the mental health crisis as a “Trojan horse” to introduce liberal ideas about sexual and racial identity. She is also concerned that schools lack the expertise to treat students’ mental illnesses.

“Social-emotional well-being has become an excuse to intervene in children’s lives in the most intimate, dangerous and irresponsible way,” Nomani said, “because they are in the hands of people who are not trained professionals.” .”

Despite unprecedented funding, schools are struggling to hire counselors, mirroring shortages in other American industries.

Goshen Junior High School in northwest Indiana has been struggling to fill the vacancy of a counselor who left last year when student anxiety and other behavioral issues were “off the charts,” said Jan Desmarais-Morse, one of the two counselors left at the school. , with a number of cases of 500 students each.

“One person trying to meet the needs of 500 students?” said Desmarais-Morse said. “It is impossible.”

The American Association of School Counselors recommends a ratio of 250 students per school counselor, which few states come close to meeting.

For the 2020-21 school year, only two states — New Hampshire and Vermont — met that goal, according to an Associated Press analysis of data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Some states face staggeringly high ratios: Arizona averages one counselor for every 716 students; in Michigan, 1 to 638; and in Minnesota, 1 to 592.

Also in Indiana, School City of Hammond won a grant to hire clinical therapists at its 17 schools but has been unable to fill most of the new jobs, Superintendent Scott Miller said. “Schools are stealing from other schools. There just aren’t enough workers to go around.” And despite more funding, school salaries can’t compete with private counseling practices, which are also overwhelmed and trying to hire more staff.

Another challenge for schools: identifying struggling children before they enter an emotional crisis. In the Houston Independent School District, one of the largest in the country with 277 schools and nearly 200,000 students, students are asked each morning to hold up their fingers to show how they feel. A finger means that a child is deeply hurt; five means that she or he is feeling great.

“It’s identifying your wildfires early in the day,” said Sean Ricks, the district’s senior crisis intervention manager.

Houston teachers now teach mindfulness lessons, with ocean sounds played through YouTube, and a chihuahua named Luci and a cockapoo named Omi have joined the district’s crisis team.

Grant funds helped Houston build relaxation rooms, known as Thinkeries, at 10 schools last year, costing about $5,000 each. District data shows that schools with Thinkeries, which sport bean bag chairs and warm-colored walls, saw a 62% drop in calls to a crisis line last year, Ricks said. The district is building more this year.

But the rooms themselves are not a panacea. For calm rooms to work, schools must teach students to recognize when they feel angry or frustrated. They can then use the space to relax before their emotions flare, said Kevin Dahill-Fuchel, executive director of Counseling in Schools, a nonprofit organization that helps schools bolster mental health services.

In the last days of summer vacation, an artist who painted a mural of a giant moon over mountains was getting the finishing touches on a “Well Space” at the University of California’s Irvine High School. Potted succulents, jute rugs, Buddha-shaped figurines and a hanging egg chair brought an unschool feel. When school starts this week, the room will be staffed full time with a counselor or mental health specialist.

The goal is to normalize the idea of asking for help and give students a place to reset. “If they can refocus and refocus,” Blakely said, “then after a short break, they can go back to their classrooms and be ready for deeper learning.”

Read the Last News Y Breaking news here

.