Cambridge: This has been revealed in a recent study Robots may be more effective than parent report or self-reported tests in diagnosis Mental health disorders Among the youth.

Roboticists, computer scientists and Psychiatrists from University of Cambridge The study was conducted with 28 children between the ages of eight and 13 and administered a series of standards to a child-sized humanoid robot. Psychological A questionnaire to assess the mental well-being of each participant.

Children were willing to trust the robot, in some cases sharing information with the robot that they had not yet shared through the standard assessment method of online or in-person questionnaires. This is the first time that robots have been used to assess the mental state of children.

The researchers say robots can be a useful addition to traditional methods of mental health assessment, although they are not intended to be a substitute for professional mental health help. The results will be presented today (September 1) at the 31st IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) in Naples, Italy.

Meanwhile Nationwide outbreak of Kovid-19, homeschooling, financial pressures, and isolation from peers and friends affected the mental health of many children. However, even before the pandemic, anxiety and depression are on the rise among children in the UK, but resources and support to address mental health are severely limited.

Professor Hatice Guns, who leads the Affective Intelligence and Robotics Laboratory in Cambridge’s Department of Computer Science and Technology, has been studying how socially assistive robots (SARs) could be used as mental wellbeing ‘coaches’ for adults, but in recent years she has Also studies how it can be beneficial for children.

“After I became a mother, I became more interested in how children express themselves as they grow up and how that might overlap with my work in robotics,” Gunes said. “Kids are very tactile, and they’re drawn to technology. If they’re using a screen-based tool, they withdraw from the physical world. But robots are perfect because they’re in the physical world. They’re more interactive. , so kids is more busy.”

Along with colleagues from Cambridge’s Department of Psychiatry, Goons and his team designed an experiment to see if robots could be a useful tool for assessing mental well-being in children.

Nida Itrat Abbasi, first author of the study, said, “There are times when traditional methods may not capture mental well-being deficits in children, because sometimes the changes are so subtle.” “We want to see if robots can help with this process.”

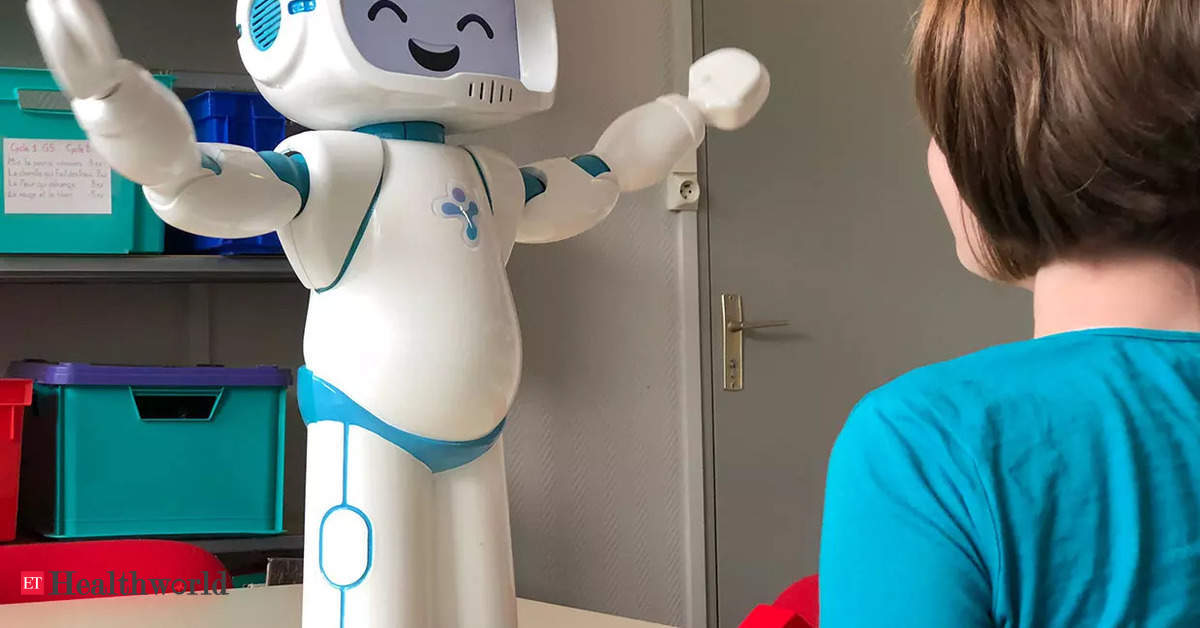

For the study, 28 participants between the ages of 8 and 13 took part in a 45-minute one-on-one session with the Nao robot, a humanoid robot about 60 centimeters tall. A parent or guardian observes from an adjacent room, along with members of the research team. Before each session, children and their parents or guardians completed a standardized online questionnaire to assess each child’s psychological well-being.

During each session, the robot performed four different tasks:

1) asked open-ended questions about happy and sad memories in the past week;

2) Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) administered

3) administered a picture task inspired by the Children’s Apperception Test (CAT), where children are asked to answer questions related to shown pictures; And

4) Administered the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) for generalized anxiety, panic disorder and low mood.

Children were divided into three different groups following the SMFQ, according to how they were struggling with their mental well-being. Participants interacted with the robot throughout the session by talking to it or touching sensors on the robot’s arms and legs. Additional sensors tracked participants’ heart rate, head and eye movements during the session.

All of the study participants said they enjoyed talking to the robot: some shared information with the robot that they would not have shared in person or on an online questionnaire.

The researchers found that children with different levels of well-being anxiety interacted with the robot differently. For children who may not be experiencing mental well-being-related problems, the researchers found that interacting with the robot led to more positive response ratings to the questionnaire. However, for children experiencing well-being-related concerns, the robot may have enabled them to reveal their true feelings and experiences, leading to more negative response ratings to the questionnaire.

“Since the robot we use is child-sized and completely non-threatening, children can see the robot as trustworthy, they feel they won’t get into trouble if they share secrets with it,” Abbasi said. “Other researchers have found that children are more likely to disclose private information such as when they are being bullied, for example to a robot than they are to adults.”

The researchers say that while their results show that robots can be a useful tool for psychological assessment of children, they are not a substitute for human interaction.

“We have no intention of replacing psychologists or other mental health professionals with robots, as their skills exceed anything a robot can do,” co-author Dr. Michael Spittel said. “However, our work suggests that robots can be a useful tool to help children open up and share things they might not be comfortable sharing at first.”

The researchers say they hope to expand their survey in the future by including more participants and following them over time. They are also investigating whether similar results can be achieved if children interact with the robot via video chat.

The research was partially supported Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), Vol UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), and NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.