NEW YORK — Ofek Preis won’t walk to class by herself anymore. She’s afraid of being harassed for being Jewish.

“I’m just so burnt out from this. I just want to go to class and have a normal class. Then I remember that there is so much antisemitism here. It can be really debilitating,” said Preis, a 21-year-old senior at State University of New York (SUNY) New Paltz.

“It’s shocking and triggering. You start to feel you have no control of your learning environment; you feel unsafe everywhere,” she told The Times of Israel.

Preis isn’t alone: Jewish students across the United States report being excluded from campus organizations, targeted on social media and harassed in classes by students and professors alike. Additionally, they’ve seen dormitories and sidewalks vandalized with swastikas, and buildings plastered with flyers that equate Birthright trips to Israel with genocide and call for Zionists to “fuck off.”

Yet, often lost in the coverage of these incidents is the emotional toll they take on the Jewish students.

One in three college students personally experiences antisemitic hate during the academic year, according to an October 2021 survey conducted for the Anti-defamation League (ADL) and Hillel International. The survey found that 32 percent of Jewish students experienced antisemitism directed at them, and 79% of those students reported that it happened to them on more than one occasion.

Additionally, over 350 anti-Israel incidents occurred on campuses nationwide during the academic year 2021-2022, according to the ADL’s annual Campus Report. The most common means of harassment involved excluding Zionist students, supporting anti-Israel violence and perpetuating antisemitic tropes, according to the report.

“Hate crimes, including those derived from antisemitism, can have dangerous physical, psychological and societal consequences. Research demonstrates that acts of discrimination affect the immune systems of victims and those who witness hateful acts, and the effects of hate crimes change attitudes and behaviors at a societal level for years,” says a June 2021 American Psychological Association statement.

For Preis, the ordeal began after she transferred to SUNY New Paltz from SUNY Geneseo in the fall semester of 2021.

An Israeli-American, Preis was allegedly kicked out of New Paltz Accountability, a sexual-assault survivors’ support group, together with classmate Cassie Blotner, for posting about their Jewish identity on social media. Accused of white supremacy, the girls were targeted on the YikYak social media platform in the spring of 2022 with an anonymous post encouraging students to spit on “the Zionists.”

Pilloried on social media and vilified on campus, Preis said the situation became unbearable. Jittery, anxious, and unable to concentrate, she took most of her classes online for several weeks. She also moved into an off-campus apartment. The decision helped her emotionally but not academically.

Once a double major in political science and sociology, Preis said she fell behind in her studies. Forced to choose between graduating later to make up political science credits or dropping it as one of her two majors, she’s now a sociology major with a political science minor.

“It’s hard to muster up the energy to just get through my day. As a sexual assault survivor it was already a struggle, but this [antisemitism] added another layer to feeling that our safety and well-being is not protected here,” Preis said.

Illustrative: Anti-Israel, pro-Palestinian activists in New York City, May 15, 2021. (Luke Tress/Times of Israel)

The US Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights is now investigating SUNY New Paltz for not protecting Jewish students and addressing campus antisemitism. The investigation will determine whether the university violated Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination based on race and religion.

“We unequivocally condemn any attacks on SUNY students who are Jewish, and we will not tolerate anti-Semitic harassment and intimidation on campus,” says to a SUNY New Paltz statement, which adds that the university will “continue our active engagement to support our Jewish students and employees around the rise of antisemitism.”

The Department of Education is also investigating complaints against the University of Vermont (UVM), University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and University of Southern California (USC). The Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, a legal advocacy group, filed the complaints with Jewish on Campus, a student-run nonprofit organization.

“When someone experiences antisemitism and then feels the university won’t do anything, it makes you feel sort of stuck in that experience,” said Julia Jassey, a fourth-year at the University of Chicago and co-founder of Jewish on Campus.

Jassey said she too experienced antisemitism on campus. For example, on Instagram last February, the University of Chicago chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) told students not to take “Shitty Zionist classes” and to “Support the Palestine movement for liberation by boycotting classes on Israel or those taught by Israeli fellows.”

Hiding in plain sight

“I think people need to realize that antisemitism is incredibly painful for these students. This is not what college is supposed to be,” said Alyza Levin, president of the Brandeis Center.

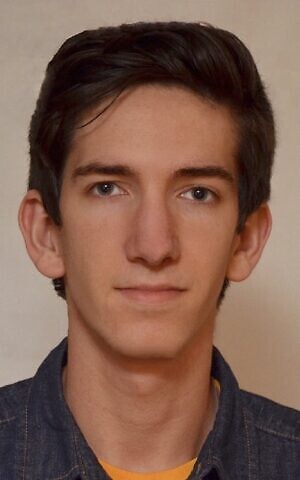

When Micah Gritz, a junior at Tufts University, goes to class he makes sure to tuck his Star of David under his shirt to avoid antisemitic harassment. (Courtesy: Micah Gritz/ Photo credit: Shahar Azran/ WJC)

“The bad news is everything you’re hearing about rising antisemitism is true. The good news is, you’re hearing about it. Denying it or downplaying it only compounds the anxiety students are feeling. It makes them think maybe it’s not real, or maybe they should hide who they are, which is not an acceptable reality,” she added.

However, hiding one’s identity is the reality for many students, including Tufts University junior Micah Gritz.

The 20-year-old international security and Jewish studies major tucks his Star of David necklace under his shirt whenever he gets to class. Before university, he never thought twice about the necklace.

That changed before move-in day of his freshman year. Gritz was one of many incoming undergraduates who sought to connect with fellow classmates on the social media platform GroupMe.

“We were chatting on it and then someone happened to mention they were Jewish. ‘Israel or Palestine?’ came the response,” said Gritz.

Once on campus he heard comments like, “You’re Jewish, you must be rich,” or “So you kill Palestinian children, right?” A professor in one of Gritz’s political science classes also insinuated that the Jewish lobby controls the government, he said.

“Sometimes I’d push back, but you can become exhausted and burnt out fighting for your identity. Sometimes you just need to prioritize your mental health,” Gritz said.

Getting involved with Jewish on Campus as its chief operating officer helped Gritz cope. Refraining from social media also helps, he said, adding that he uses Instagram infrequently and keeps his Twitter account private, primarily using it to follow the news.

Anxious and angry

That around 2,000, or 20%, of UVM’s 11,626 undergraduate students are Jewish was a draw for one student, who, fearing a backlash, spoke on condition of anonymity.

“It was so important to me to go to a school with a strong Jewish presence that I wrote about it for my college application essay,” said the UVM junior.

When she arrived at the bucolic school situated a mile from Lake Champlain, she appreciated the variety of student organizations. Some were dedicated to climate change, others to books. Some to crafts, others to social justice.

Her excitement soon evaporated.

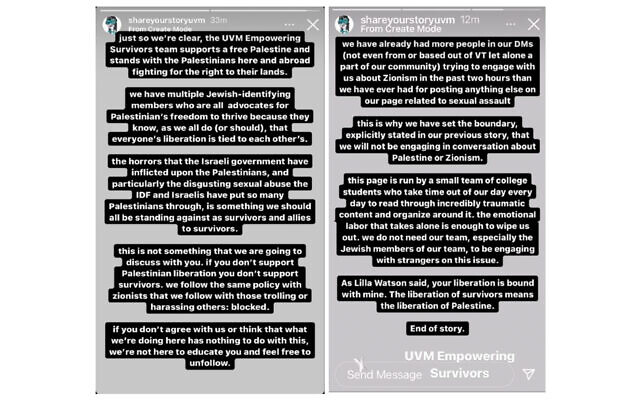

In May 2021, UVM Empowering Survivors, a sexual assault survivor support group, posted antisemitic comments on Instagram. Then a university teaching assistant reportedly targeted student supporters of Israel on Twitter. For example, on April 5, 2021, the TA wrote, “is it unethical for me, a TA, to not give zionists credit for participation??? i feel its good and funny, -5 points for going on birthright in 2018, -10 points for posting a pic with a tank in the Golan heights, -2 points just cuz i hate ur vibe in general.”

An Instagram post from a University of Vermont sexual assault survivors support group announcing the exclusion of Zionists. (Courtesy)

The university and its president, Suresh Garimella, declined to comment about the school’s handling of claims of antisemitism.

Instead, the president’s office referred to Garimella’s statement regarding the Title VI investigation, in which he said the media coverage of the Department of Education’s investigation “has painted our community in a patently false light.”

“UVM is home to a strong and vibrant Jewish community and is recognized as a place where — year after year — many Jewish students, faculty, and staff choose to study, teach, conduct research, practice medicine, and work,” the statement said.

The UVM junior found no solace in his statement.

University of Vermont President Suresh Garimella speaks with reporters on Monday, July 1, 2019, in Burlington, Vermont. (AP/Lisa Rathke)

“Just because a school has a big Jewish community doesn’t mean there isn’t antisemitism outside of those spaces. It got harder to be a Jew outside of those spaces,” she said. “I’m no longer comfortable sharing my Jewish identity in class. I’m scared to bring it up during discussion, even though everyone else is free to talk about their identity and not feel intimidated.”

Liora Rez, executive director of StopAntisemitism, said Garimella’s email is another example of an administration’s failure to act.

“They are not protecting the mental health of Jewish students,” Rez said. “So many of these students feel tremendous insecurity. Some ultimately feel the need to hide their Jewish identity or support for Israel. On the macro level that leads to stress and many students have a tough time throughout the day.”

According to the watchdog group’s latest report, 55% of respondents answered “yes” when asked if they’ve experienced some form of antisemitism at their school. Only 28% of students said they feel their school administration takes antisemitism and the protection of Jewish students seriously.

Lingering effects

Rose Ritch graduated from USC two years ago. Her experiences there still reverberate.

It was August 2020 and Ritch, then a rising senior, was elated. She’d just been elected undergraduate student government vice president. Her joy was short-lived.

Some students launched an impeachment campaign. Multiple Instagram posts called her a racist for supporting Israel. Tweets celebrated “the zionists from usc and usg getting relentlessly cyberbullied.”

“It escalated like a tornado. I was so nauseous from anxiety. I couldn’t eat for eight days. It was hard to sleep. It definitely was not a healthy moment in my life,” said the 24-year-old Ritch.

Rose Ritch graduated from USC two years ago; her experience with antisemitism still haunts. (Courtesy: Rose Ritch)

Isolation compounded the stress. It was the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and she was living alone. A steady stream of supportive texts, phone calls and video calls helped, “but a hug would have been nice,” she said.

Although some in the administration were sympathetic, there was no public condemnation of the harassment, Ritch said. She weighed her options.

“People said if I stayed I would win, and if I left I would be letting them win. It was presented as a binary choice,” Ritch said. “I realized I wouldn’t be a successful student leader, student or person if I stayed. Winning for me was canceling out the noise. I had to take my physical and mental health into account.”

The harassment continued.

She’d be in psychology class — held on Zoom because of pandemic measures — when private messages would pop up calling her a racist, she said.

Ritch welcomes the Title VI investigation into USC as well as the university’s announcement that it is developing partnerships with national organizations including the Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Committee.

Nevertheless, she remains troubled.

“It was a traumatic experience and impacted me mentally for a lot longer than I care to admit. I’m much more cognizant that there are people out there who don’t like that I hold this identity,” she said.

Changing the scenery

Some Jewish students like Gritz choose to stick it out. Others, such as Avi Zatz, decide enough is enough. The agroecology major transferred from UVM to the University of Florida this year, ahead of UVM’s Title VI investigation.

“I love it here. The administration is supportive. People are comfortable being who they are and bigotry is shut down quickly, where at UVM it was accepted,” Zatz, a junior, said of his new school where of the 34,881 undergraduates, 18%, or just over 6,000, are Jewish.

Avi Zatz says he transferred to University of Florida from the University of Vermont because of antisemitism. (Courtesy: Avi Zitz)

Zatz said he felt something was amiss at UVM when students marched down Burlington’s main street in support of BDS during the High Holy Days in 2021.

“It was uncomfortable. There were also really popular clubs on campus that I wasn’t able to join because of my background,” he said. For example, the UVM Book Club, a university-recognized student club, has a group “University of Vermont Revolutionary Socialist Union.” In May 2021 that group publicly announced it would ban Zionists.

No longer comfortable wearing anything that might identify him as Jewish, Zatz went to the administration.

“Long story short, they didn’t care. They made it clear they were not going to condemn antisemitism,” Zatz said. “I felt isolated and insecure. I thought I’m not supported and no one is being held to account. I didn’t know what to expect in college, but nobody expects to be excluded based on their background.”

While the Department of Education continues its investigations and antisemitic incidents continue unabated, SUNY New Paltz’s Preis said she hopes people will consider the emotional toll antisemitism takes on students.

“This will follow me, this feeling that our safety and well-being as a Jewish student is not considered,” Preis said. “All of it has made me question why I am here in America studying, whether I even want to stay here after I graduate. I’m not sure I see a future here anymore.”

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘272776440645465’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

var comment_counter = 0;

window.fbAsyncInit = function() {

FB.init({

appId : ‘123142304440875’,

xfbml : true,

version : ‘v5.0’

});

FB.AppEvents.logPageView();

FB.Event.subscribe(‘comment.create’, function (response) {

comment_counter++;

if(comment_counter == 2){

jQuery.ajax({

type: “POST”,

url: “/wp-content/themes/rgb/functions/facebook.php”,

data: { p: “2848839”, c: response.commentID, a: “add” }

});

comment_counter = 0;

}

});

FB.Event.subscribe(‘comment.remove’, function (response) {

jQuery.ajax({

type: “POST”,

url: “/wp-content/themes/rgb/functions/facebook.php”,

data: { p: “2848839”, c: response.commentID, a: “rem” }

});

});

};

(function(d, s, id){

var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0];

if (d.getElementById(id)) {return;}

js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id;

js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js”;

fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);

}(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’));