It’s that time of year again when the Finance Minister presents the Union Government’s spending and fundraising plans for the next fiscal year, popularly known as the Union budget. This comes against the backdrop of the Covid pandemic and reports of significant increase in mental Health problems in India. In October 2021, a study in the Lancet reported a 35 percent increase in mental health problems in India. In the same month, a UNICEF The survey found that “about 14 per cent of 15-24 year olds in India, or 1 in 7, reported that they often felt depressed or had little interest in doing things”, exacerbated, among other things, by the continuous closures of schools and universities. In November 2021, the government’s National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) annual report showed that suicides in India increased by an alarming 10 percent in 2020 during the pandemic: almost 400 Indians died by suicide each day in 2020 .

Even before the pandemic, there was a severe shortage of mental health services in India. The National Mental Health Survey in 2016 reported that almost 70-80 percent of people with mental illness in India received no treatment. This has probably been exacerbated during the pandemic.

Mental health financing has traditionally been neglected in our health budgets. For years, the mental health sector received barely 1 percent of the funds allocated to the health sector, despite the fact that mental health problems probably account for nearly 10 percent of health-related morbidity and healthy years of life lost due to disease. Analysis of last year’s Union Budget by my Center showed that Rs 932 crore was allocated to mental health, Rs 597 crore through direct funding for Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHFW) and Rs 334 crore indirectly through programs for people with disabilities administered by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MOSJE). This amount constituted only 0.81 percent of the entire MOHFW health budget. However, of the Rs 597 crores of direct mental health funding for the MOHFW, 93% was allocated to the three central mental health institutions and only 7% (Rs 40 crores) was allocated to the National Health Program mind across the country. the whole country

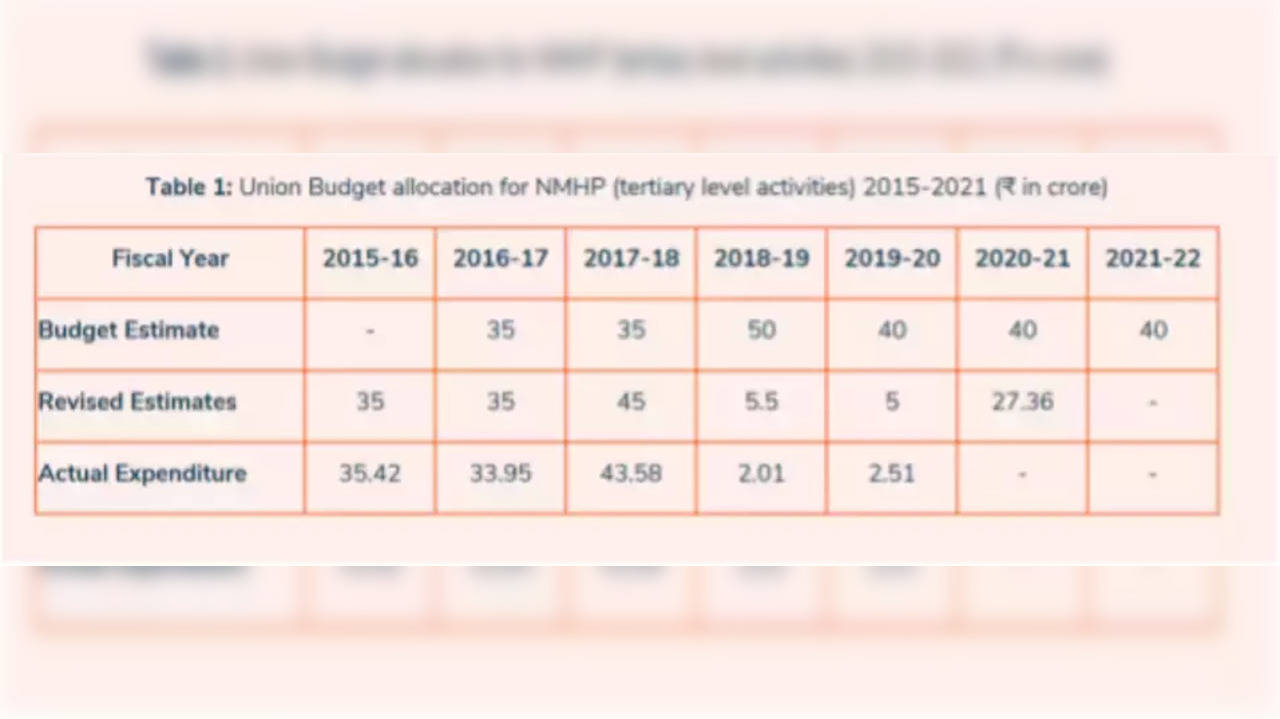

In all fairness, the Ministry of Finance can point to the abysmal utilization of even the meager funds allocated to the National Mental Health Program (see Figure 1 below). Almost 95 percent of this meager amount was returned unspent in the years 2018-2020. The revised estimates for 2020-21 were lowered by 30 per cent, presumably due to a lack of buy-in from the Ministry of Health. It points to a serious implementation problem in the Ministry of Health. Unless these are addressed, additional funding allocations will not result in an improvement in the availability of mental health services across the country. We must also remember that health is primarily a state issue and states need to step up and increase funding for mental health in their state health budgets.

So what can the Minister of Finance do? In the short term, the lack of absorptive capacity of the Ministry of Health to use the funds allocated to mental health presents a serious challenge. A sudden bolus of increased mental health funding to the Ministry of Health will not result in an improvement in mental health services tomorrow, and will in fact backfire, as funds will be returned unspent, as we have seen in previous years .

The Finance Minister should take a more medium-term view and announce a plan for gradual increases in funding over the next three to five years. Along with this, there is a need to develop the administrative capacity of the Ministry of Health to use the funds. Over the next five years, the Finance Minister must ensure that at least 10 percent of the Ministry of Health allocation is spent on mental health (from the current 0.8 percent). This can easily be done without cutting existing budgets for other areas of health, by requiring that a greater proportion of future health funding increases go to mental health. The Finance Minister should also note that the Mental Health Act 2017, which was legislated by this Government, has provisions on the right to access mental health care from government health services and obliges the Government to increase funding for mental health services.

In the immediate short term, many civil society organizations are better positioned to provide mental health services in the community, as shown by the programs run by Banyan, Ishwar Sankalpa and my own organization in different parts of the country, including Tamil Nadu, West Bengal. and Gujarat. These programs have been highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO) among the 25 most innovative community programs in the world and work at the grassroots level. There is an opportunity to expand these programs by exploring public-private partnerships with civil society organizations.

The Finance Minister should also look at areas where additional funding is not required but could dramatically improve the availability of affordable mental health services. For example, the Ayushman Bharat scheme has 13 mental health care packages, but these are currently only available from public health hospitals, unlike other health packages that can also be provided by private health providers. Expanding the coverage of these mental health packages to private mental health providers will increase access, without an additional allocation of mental health funds, as this could affect Ayushman Bharat’s existing funding pool.

Similarly, with children’s mental health, an additional mental health boost in existing programs such as the Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) could pay immediate dividends rather than establishing a separate children’s mental health program . Mental health is one of the 7 focus areas for community health workers at Health and Wellness Centers (AB-HWCs) and increased allocations for training these community workers to provide effective mental health services can improve the accessibility of mental health services in rural areas. areas

(Dr. Soumitra Pathare, is a psychiatrist by training and director of the Center for Mental Health Law and Policy, Indian Law Society, Pune, India. He was a member of the Policy Group that drafted India’s first mental health policy. India in 2014. His work covers the areas of mental health policy, expanding community-based mental health services, suicide prevention, and mental health legislation.)

(Disclaimer: The views expressed in this column are those of the author. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of www.timesnownews.com.)

.