Fifteen-year-old Jordyne Lewis was stressed.

The Harrisburg, North Carolina, high school sophomore was overwhelmed with schoolwork, never mind the uncertainty of living in a pandemic that has dragged on for two long years. Despite his challenges, he never went to his school counselor or sought out a therapist.

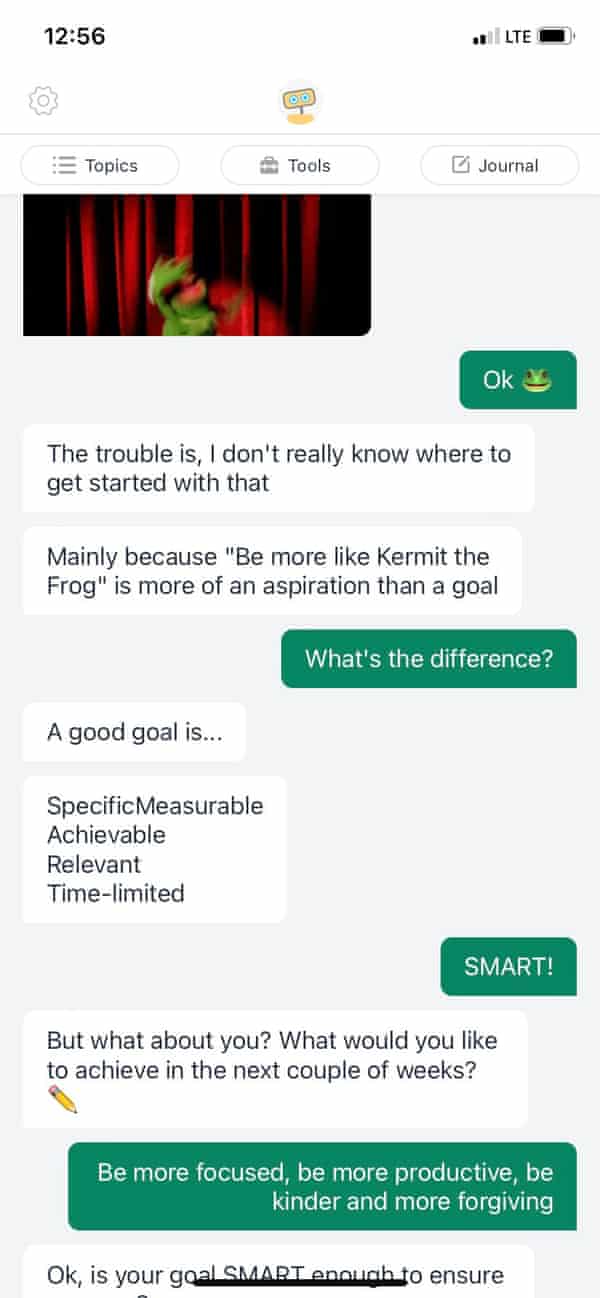

Instead, he shared his feelings with a robot. aybot to be precise.

Lewis has struggled to cope with the changes and anxieties of pandemic life and for this outgoing teenager, loneliness and social isolation were some of the biggest struggles. But Lewis didn’t feel comfortable going to a therapist.

“I have a hard time opening up,” he said. But did Woebot do the trick?

Chatbots use artificial intelligence similar to Alexa or Siri to engage in text-based conversations. Its use as a wellness tool during the pandemic, which has worsened the youth mental health crisis – has proliferated to the point where some researchers are wondering if robots could replace living, breathing school counselors and trained therapists. That’s a concern for critics, who say they’re a band-aid solution to psychological suffering with a limited body of evidence to support their effectiveness.

“Six years ago, this whole space was not so fashionable. It was considered almost crazy to do things in this space,” said John Torous, director of the division of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. When the pandemic hit, he said people’s appetite for digital mental health tools grew dramatically.

Throughout the crisis, experts have been sounding the alarm about a increased depression and anxiety. During his State of the Union address earlier this month, Joe Biden called out the mental health challenges of young people an emergencynoting that “students’ lives and education have been turned upside down.”

Digital wellness tools like mental health chatbots have stepped in with the promise of filling gaps in America’s overburdened and underresourced mental health care system. As much as two-thirds of American children experience traumaHowever, many communities lack mental health providers who specialize in treating them. National estimates suggest there are fewer than 10 child psychiatrists per 100,000 youth, less than a quarter of the staffing level recommended by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

School districts across the country have recommended the free Woebot app to help teens cope, and thousands of other mental health apps have flooded the market with the promise of a solution.

“The pandemic hit and this technology basically took off. Everywhere I look now there is a new chatbot that promises to offer new things,” said Serife Tekin, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Texas at San Antonio, whose research has challenged the ethics of AI-powered chatbots in mental health care. When Tekin tried Woebot herself, she felt that her developer promised more than the tool itself could deliver.

Body language and tone are important to traditional therapy, Tekin said, but Woebot doesn’t recognize such nonverbal communication.

“It’s nothing like how psychotherapy works,” Tekin said.

PPsychologist Alison Darcy, founder and president of Woebot Health, said she created the chatbot in 2017 with young people in mind. Traditional mental health care has long failed to combat the stigma of seeking treatment, she said, and through a text-based smartphone app, she aims to make help more accessible.

“When a young person walks into a clinic, all the trappings of that clinic, the white coats, the advanced degrees on the wall, are really something that threatens to undermine the treatment, not engage the young people in it,” he said in a statement. interview. Rather than share intimate details with another person, he said young people, who have spent their entire lives interacting with technology, might feel more comfortable solving their problems with a machine.

Lewis, the North Carolina student, agreed to use Woebot for about a week and shared her experiences for this article. Lewis, a sophomore in Advanced Placement classes, was feeling “nervous and overwhelmed” about the upcoming tests, but she reported feeling better after sharing her struggles with the chatbot. Woebot urged Lewis to challenge her negative thoughts and offered her breathing exercises to calm her nerves. She felt that the chatbot circumvented the traditional in-person therapy conditions that made her uneasy.

“It’s a robot,” he said. “It is objective. He can’t judge me.

Critics, however, have offered reasons to be cautious, noting faultsquestionable data collection and privacy practices Y defects on existing research on its efficacy.

Academic studies co-authored with Darcy suggest that Woebot decreases symptoms of depression among college students, it is an effective means intervention for postpartum depression and can reduce substance use. Darcy, who taught at Stanford University, acknowledged that his role in the research presented a conflict of interest and said additional study was needed. After all, he has big plans for the future of the chatbot.

The company is seeking approval from the US Food and Drug Administration to use its chatbot to treat teen depression. Darcy described the free Woebot app as a “lightweight wellness tool.” But Darcy said a separate, prescription-only chatbot designed specifically for teens could give them an alternative to antidepressants.

Not all professionals are against the automation of therapy. In Ohio, researchers at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and the University of Cincinnati partnered with the chatbot developer. Wysa to create a “Covid Anxiety” chatbot specially built to help teens cope with unprecedented stress.

The researchers hope that Wysa can expand access to mental health services in rural communities that they lack child psychiatrists. Teenage psychiatrist Jeffrey Strawn said the chatbot could help young people with mild anxiety, allowing him to focus on patients with more significant mental health needs.

He says it would have been impossible for the mental health care system to help all students with anxiety even before Covid. “During the pandemic, it would have been super unsustainable.”

‘The easy fix’

The researchers are concerned that the apps may have difficulty identifying young people in a serious crisis. In 2018, a BBC investigation found that in response to the message “I’m being forced to have sex and I’m only 12”, Woebot responded by saying, “I’m sorry you’re going through this, but it also shows me how much you care.” connection and that’s really beautiful.”

There are also privacy concerns: digital wellbeing apps are not subject to federal privacy rulesand in some cases share data with third parties such as Facebook.

Darcy, the founder of Woebot, said her company follows “hospital-grade” security protocols with its data, and while natural language processing is “never 100% perfect,” they have made significant upgrades to the algorithm in recent years. . Woebot is not a crisis service, she said, and “we need all users to acknowledge it” during a mandatory intro built into the app. Still, she said the service is critical to solving access problems.

“There is a very big and urgent problem right now that we need to address in ways additional to the current health system that has failed so many, particularly underserved people,” he said. “We know that young people in particular have much more access problems than adults.”

Tekin, of the University of Texas, offered a more critical view, suggesting that chatbots were simply stopgap solutions that don’t solve systemic problems like limited access and patient hesitation.

“It’s the easy fix,” he said, “and I think it might be motivated by financial interests, to save money, rather than finding people who can provide genuine help to students.”

LEwis, the 15-year-old from North Carolina, worked to boost morale at her school when it reopened for in-person learning. When the students arrived on campus, they were greeted with positive messages written in sidewalk chalk welcoming them.

She is a young activist with the non-profit organization Sandy Hook Promise, which trains students to recognize the warning signs that someone might hurt themselves or others. The group, which operates a anonymous tip line in schools Nationally, it has seen a 12% increase in reports related to student suicide and self-harm during the pandemic compared to 2019.

Lewis said efforts to lift the spirits of her classmates have been an uphill battle, and the stigma surrounding mental health care remains a major concern.

“I also struggle with this, we have a problem asking for help,” he said. “Some people feel like it makes them feel weak or hopeless.”

With Woebot, he said the app lowered the bar to help, and he plans to continue using it. But he decided not to share certain sensitive details due to privacy concerns. And while she’s comfortable talking to the chatbot, that experience hasn’t eased her reluctance to entrust her problems to a human.

“It’s like the springboard to get help,” he said. “But it’s definitely not a permanent solution.”